Introduction

Employee health issues contribute to higher organizational costs through absenteeism, turnover, and healthcare expenses (Miller & Haslam, 2009). As a result, there has been a growing emphasis on workplace stress management and health promotion programs in recent years (Tetrick & Winslow, 2015). From this context of proactive healthcare, emerged the concept of health-promoting leadership (HPL), which aims to promote and support the health of employees (Eriksson et al., 2011). Examples of HPL include traditional good leadership behaviors (e.g., social support, positive feedback; Winkler et al., 2014), as well as specific health-promoting behaviors (e.g., advocating the value of health and incorporating health-oriented activities; Franke et al., 2014). Research demonstrates the benefits of HPL on employee health, wellbeing, job attitudes, and leader-employee relationships (Franke et al., 2014; Milner et al., 2013; Nielsen et al., 2019; Zhang & Liu, 2022). However, few studies examined the impact of HPL on job performance. Job performance is defined as employee behaviors and outcomes that contribute to organizational goals (Carlos & Rodrigues, 2015). Job performance can be broken down into two components: task and contextual. Task performance is one’s competency in performing job tasks; contextual performance is engaging in behaviors that support the organization such as cooperation and persistent effort (Carlos & Rodrigues, 2015).

HPL may affect employees’ job performance through its impact on wellbeing, which is defined as the quality and value of a person’s life (Maggino, 2014). Research demonstrates a clear link between wellbeing and job performance (Dannheim et al., 2021; Jackson & Frame, 2018). The connection between HPL, wellbeing, and job performance can be grounded in three theories: the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll et al., 2018), the Job Demands-Resources model (JD-R; Demerouti et al., 2001), and the Social Exchange theory (Homans, 1958). The JD-R and COR theories state that individuals strive to maintain the resources they have while also pursuing new resources (Hobfoll et al., 2018). Health-promoting leaders are shown to enhance employees’ health-related resources (i.e., knowledge, awareness, access), which affects their wellbeing (Franke et al., 2014: Dannheim et al., 2021). Related to resources, the JD-R model suggests that positive attitudes and behaviors (wellbeing) are influenced by job resources such as HPL, which in turn influence positive results (performance) (Demerouti et al., 2001). The Social Exchange theory (Homans, 1958) expresses building mutually beneficial relationships and achieving desired outcomes for both parties through reciprocal exchanges (Reader et al., 2016). When leaders invest in their employees’ health, employees demonstrate enhanced wellbeing, which then, encourages them to contribute back to the organization through performance (Miller & Haslam, 2009). Thus, it is thought that wellbeing might play a mediating role in the relationship between HPL and job performance.

However, most studies on HPL examine bivariate relationships with outcomes, lacking an explanation of the underlying mechanisms of the relationship. Moreover, most research on HPL comes from European countries such as Germany and Sweden (e.g., Eriksson et al., 2010; Gurt et al., 2011; Vincent-Höper & Stein, 2019) which are found to outperform Canada and the United States on overall health systems such as access to health care, equity, and health outcomes (Schneider et al., 2017). Thus, international research may not be generalized to a North American context. This research aims to fill these gaps by investigating the relationship between HPL and job performance, mediated by wellbeing, while focusing on the North American context.

Health Promoting Leadership

The general perspective of HPL is defined as effective leader behaviors that promote employee’s health (Yao et al., 2021). Winkler et al. (2014) suggested that leaders promote health and wellbeing through social support, task-related communication, and positive feedback. Additionally, research by Vincent Hoper and Stein (2019) demonstrated that positive leadership behaviors enhance employee wellbeing, yet it fails to address the role of specific leader behaviors on employee health. The specific perspective defines HPL as a leadership style where leaders motivate employees to be healthy, enhance employees’ health awareness, and take responsibility for the health of their employees (Franke et al., 2014; Yao et al., 2021). Jiménez et al. (2016) argued that health-promoting leaders take a holistic view of health, make efforts to design a healthy workplace and a health-promoting culture, and value their own and employees’ health. Research from the specific perspective of HPL indicates that leaders are important facilitators of individual- and environmental-focused health-promoting activities (Franke et al., 2014). Therefore, the specific perspective of HPL is shown to have both a direct and indirect impact on employee health, while the general perspective only suggests an indirect impact.

Some scholars have incorporated both general good leadership and specific health-promoting activities, arguing that both together are most effective at enhancing employee wellbeing (Gurt et al., 2011). Nevertheless, despite its proposed positive effects, the general and mixed perspectives on HPL may pertain to certain limitations. For example, Nielson and Daniels (2016) revealed that employees with transformational leaders (a perspective that aligns with the general perspective of HPL) had a high rate of sickness absenteeism in their first year compared to their second year. This may be because this leadership style encourages a collectivist and internalized view of team values (Siangchokyoo et al., 2020). The current study uses the specific perspective of HPL and defines it as a leadership style that values and encourages employee health, and aims to create a health-promoting workplace. The specific perspective was chosen for this study due to the aforementioned criticism of the general and mixed perspectives.

Wellbeing Outcomes of Health-Promoting Leadership

Wellbeing can be broadly defined as the quality of a person’s life, or a state of being mentally, physically, and generally healthy (Maggino, 2014; Warr & Nielsen, 2018). Research has shown that HPL plays an important role in many employee health-related outcomes, such as greater levels of health awareness, improved state of health, less irritability, fewer health complaints, and lower levels of work-family conflict (Franke et al., 2014). A study found that HPL was negatively correlated with police officers’ level of burnout, depression, and physical complaints and positively correlated with their level of wellbeing (Santa Maria et al., 2018). This established relationship has been demonstrated across organizations and industries such as healthcare, education, public administration, finance, and low-skilled workforces (e.g., Gurt et al., 2011; Horstmann, 2018; Milner et al., 2013).

One explanation for the relationship between HPL and employee wellbeing is that HPL endorses social resources (e.g., colleague support) and task resources (e.g., autonomy) in the workplace (Bregenzer et al., 2019). According to the JD-R model (Demerouti et al., 2001), resources at work are classified as the physical, psychological, social, task-related, and organizational components that help employees achieve goals and reduce stress. According to the COR theory, individuals strive to acquire, protect, and refill valuable resources (Hobfoll et al., 2018). Health-promoting leaders tend to be more attentive to stressful working conditions and act to promote the health of their employees, which consequently helps employees acquire, protect, and replenish their resources (Franke et al., 2014). In other words, the resources provided by health-promoting leaders at work are important precursors for employee health and wellbeing. Current research on HPL largely focuses on the outcome of employee health and wellbeing. However, less is known whether HPL has a positive effect on employee performance, and whether this effect is carried through wellbeing.

Leadership Style and Job Performance

Although there is currently little research on the relationship between HPL and job performance, multiple studies have investigated the relationship between other forms of leadership, including transformational, and job performance (e.g., Nasab & Afshari, 2019). Multiple studies, including meta-analyses, have demonstrated a positive relationship between transformational leadership and job performance across organizational type, leader level, geographical region, and research design (e.g., Al-Malki & Juan, 2018; Lai et al., 2020). The relationship between leadership and job performance is often explained by the Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) theory (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). According to the LMX theory, leaders and followers form unique relationships based on their social interactions, and the quality of these interactions can affect employee outcomes such as job satisfaction, helping behaviors, task commitment, and task performance (Gerstner & Day, 1997; Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). Therefore, when a leader demonstrates qualities of a good leader (e.g., empowering employees, communicating openly, being inspirational), employees are motivated to reciprocate the exchange, which results in enhanced job performance. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that HPL will also have a positive relationship with employee performance. However, given its direct link to wellbeing and research discussed in the following section, it is plausible that the positive relationship between HPL and performance is mediated by wellbeing.

Research has demonstrated that employee wellbeing is a predictor of job performance (see Salgado & Moscoso, 2022 metanalysis; Warr & Nielsen, 2018). The relationship between employee wellbeing and job performance is often explained by the happy-productive worker hypothesis. According to this hypothesis, happy employees (determined by measures of subjective wellbeing) exhibit higher levels of job performance than unhappy employees (Wright et al., 2002). Thus, this study looks at the indirect influence of HPL on job performance through the mediational mechanism of wellbeing.

Mediating Role of Wellbeing

Existing research has shown that health-promoting leaders enhance employees’ wellbeing by demonstrating concern for their health and wellbeing, offering them a safe and supportive work environment, and providing them with accessible resources (Eriksson, 2011; Franke et al., 2014; Yao et al., 2021). In turn, the employees feel better, which makes them more willing to exert their mental, physical, and emotional resources into fulfilling their job responsibilities (Franke et al., 2014). Previous studies on leadership and job performance have supported the mediational variable of wellbeing. For example, a study by Ahmad & Al-Shbiel (2019) supported the assertion that positive leadership, specifically ethical, can create a sense of psychological wellbeing in employees, which makes employees more capable of performing better.

The mediational relationship can be best explained through the JD-R model (Demerouti et al., 2001) which suggests that positive attitudes and behaviors (wellbeing) are influenced by job resources (HPL), which in turn influences positive employee results (performance) (Demerouti et al., 2001). According to this model, job demands are linked to physiological and psychological costs such as burnout. Job resources, on the other hand, are characteristics of a job that facilitate the achievement of professional objectives, lessen the demands of the job and its consequences, and promote individual growth and development (Demerouti et al., 2001). Leadership is often regarded as either a job resource or a factor influencing resources and demands (Tummers & Bakker, 2021). For this reason, positive leadership styles such as HPL can lessen the demands of the job and promote employee growth and development, thereby reducing burnout and enhancing wellbeing. Employees will inevitably perform better at work due to their increased wellbeing brought on by the feeling that they have the resources to handle the demands of their job. This claim is bolstered by the Social Exchange theory that assumes that employees not only will have resources to perform better, but also will feel compelled to return positive treatment by increasing their efforts (Ahmad & Al-Shbiel, 2019). Based on the above outlined theory and research, it is hypothesized that employee perceptions of their wellbeing will positively mediate the relationship between their leader’s HPL behaviors and their self-rated job performance.

Method

This was a quantitative correlational study with data collected via an online survey.

Sample

A total of 119 surveys were completed by full-time employees across Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America. Of those, 77 were completed fully and used for analysis. In order to be eligible to take the survey, participants had to be at least 18 years of age, work a minimum of 30 hours per week, and have been in their current position with the same immediate supervisor for at least six months. Additionally, the participants had to be fluent in English and be located in a Western country where English is the primary language. Of the completed responses, 60% of respondents were female and 38% male, with 1% of respondents choosing not to identify a gender, and 1% identifying as non-binary. The majority (50.65%) were between 19-29 years old, followed by 30-39 (22.08%), 40-49 (10.39%), 50-59 (9.09%), and 60-70 (7.79%). Most participants completed a bachelor’s degree (40.26%), followed by 16.88% with a master’s degree, and 14.29% with a college diploma. The majority (92.21%) were from Canada, with minor representation from the United Kingdom, Australia, and the USA. Almost 42% worked more than 40 hours per week and 38.96% worked 36-40 hours per week.

Finally, most participants (80.52%) were non-managers.

Recruitment Procedures

Participants were recruited using snowball and convenience sampling, through recruitment posters with a QR code to the survey posted in local businesses such as universities, offices, and coffee shops, as well as social media platforms Instagram, Facebook, and LinkedIn. Participants were offered to enter for the chance to win one of two CAN$25 gift cards.

Measures

Health-Promoting Leadership. HPL was assessed with the Health-Promoting Leadership Conditions (HPLC) scale developed by Jiménez et al. (2016) who took inspiration from previous instruments such as the Areas of Work Life Scale (Leiter & Maslach, 1999) and the Health-Oriented Leadership (HoL) scale (Franke & Felfe, 2011). It measures a leader’s ability to create conditions that support and improve employee health. It consists of 7 dimensions (health awareness, workload, control, reward, community, fairness and value-fit) with 21 questions on a 7-point Likert scale (never (0) to always (6)). A sample item for the health awareness dimension is “My leader takes care that all employees are motivated to take care of their health”. The scale has good psychometric properties (Jiménez et al., 2016).

Wellbeing. A 29-items self-report Wellbeing Scale (WeBS) developed by Lui and Fernando (2018) assesses five distinct dimensions including physical wellbeing, financial wellbeing, social wellbeing, hedonic wellbeing, and eudemonic wellbeing. A 6-point Likert scale with responses ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (6). A sample item is “I have enough financial resources to have fun”. Internal consistency reliability and construct validity were found to be adequate to excellent in initial testing (Lui & Fernando, 2018).

Job Performance. A 29-item self-report measure of job performance (Carlos & Rodrigues, 2015) assesses two dimensions, task and contextual. A sample item includes “I’m still able to perform my duties effectively when I’m working under pressure.” A 7-point Likert scale (strongly disagree (1); strongly agree (7)) is utilized. It has satisfactory internal consistency (⍺=.75) and moderately high composite reliability (⍺=.88; Carlos & Rodrigues, 2015).

Demographics. All participants were asked about their age, gender, level of education, geographic location, and number of hours worked per week.

Results

Results of the descriptive analysis (Table 1) show no significant skew within the HPL and Job Performance scales; however, the Wellbeing scale shows a moderate negative skew of .72. Nevertheless, the bootstrapping procedure utilized during hypothesis testing is beneficial for adjusting for moderately skewed data (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). A bootstrap method yields estimates of the indirect effects and confidence intervals for those effects. This bootstrap sample was used to calculate the regression coefficient and indirect effect estimates 1,000 times. The mean and 95% confidence intervals of these 1,000 estimates were computed. The estimate is considered significant if a 95% confidence interval for the estimate does not include zero (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). HPL was used as an independent variable, wellbeing as a proposed mediator and job performance as a dependent variable.

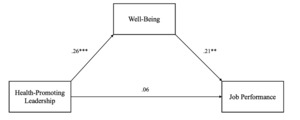

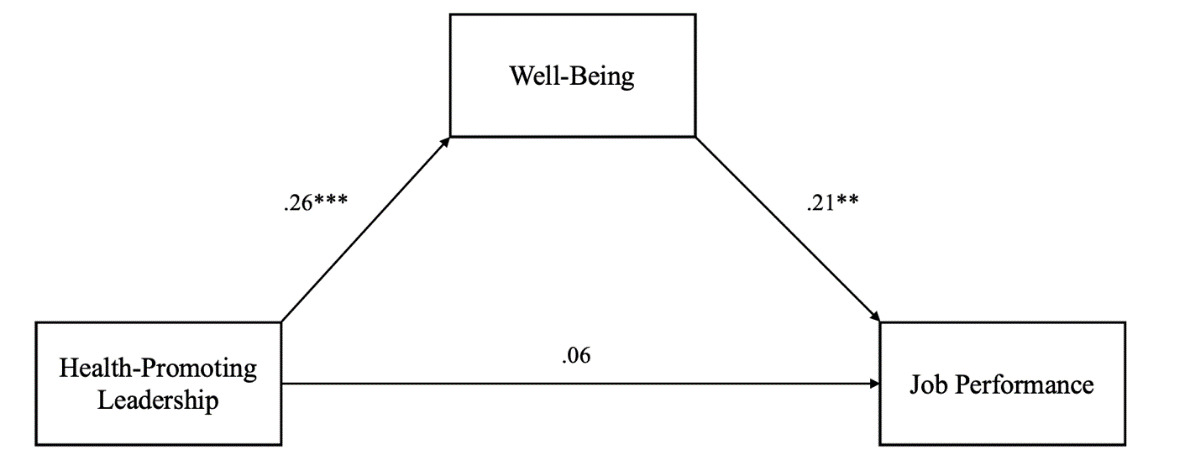

It was found that the direct effect of HPL on job performance was not significant (direct effect=.06, se=.06, p=.28). However, the direct effect of HPL on the mediator, wellbeing, was significant and positive (b=.26, se=.08, p<.001), indicating that those who rated their leaders higher on HPL were more likely to report higher levels of wellbeing than those who rated their leaders lower on HPL. The direct effect of wellbeing on job performance was also positive and significant (b=.21, se=.08, p<.01), indicating that people who experienced higher levels of wellbeing performed better on their job. The total indirect effect of HPL on job performance, which incorporated wellbeing as a mediator, was significant (indirect effect=.05, BCa 95% [.01, .13]). Based on these results, the hypothesis was supported. The findings indicate that wellbeing fully mediated the relationship between HPL and job performance (Figure 1).

Discussion

Research on HPL is growing, with several studies showing the positive effect it can have on employee health and wellbeing (e.g., Franke et al., 2014; Horstmann, 2018; Nielsen et al., 2019). The purpose of this study was to examine employee wellbeing as a mediator in the above-stated relationship. The results of this study fill the gap in existing literature and provide a profound understanding of the relationship between HPL, wellbeing, and job performance. The findings of this study suggested that employees who feel that their leader values and supports employee health perform better than those who do not. These results are consistent with existing research on leadership styles and job performance that suggest leaders may affect employee behavior that contributes to their performance (e.g., Nasab & Afshari, 2019).

As such, it does appear that HPL positively relates to job performance based on mechanisms summarized by Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) theory (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). As reflected in the LMX theory, health-promoting leaders also offer employees social-related currencies through their general good leadership behaviors and their value for their employee’s health and wellbeing. In turn, employees reciprocate through their enhanced performance. Moreover, the results of this study support the second hypothesis, signifying that wellbeing fully mediates the relationship between HPL and job performance. These results are consistent with current literature that suggests that followers of health-promoting leaders report a better state of health, fewer health complaints, (Franke et al., 2014; Santa Maria et al., 2018) and wellbeing that influences job performance (Kundi et al., 2020).

The results of this study add to current literature by specifying the relationship between HPL and job performance and considering the mediating role of wellbeing in this relationship. This is an important discovery as this mediational relationship had not been explored previously. This study provides preliminary support for the idea that wellbeing is considered an important resource for employees. As reflected in the COR theory, health-promoting leaders are also more aware of the stress-inducing factors at work and act to provide employees with resources to reduce stress and burnout (Franke et al., 2014). In turn, employees scoring high on wellbeing are shown to outperform employees scoring low on wellbeing (Bryson et al., 2017; Wright et al., 2002). These findings are best explained by the happy-productive worker thesis which suggests that happy employees display higher levels of performance-related behaviors than unhappy employees (Warr & Nielsen, 2018).

In all, the Job Demands-Resources model (JD-R) suggests that positive attitudes and behaviors (wellbeing) are influenced by job resources (HPL), which in turn influence positive employee results (performance) (Demerouti et al., 2001). Leadership is often regarded as a job resource or a factor affecting job resources and demands (Tummers & Bakker, 2021). Research suggests that when employees have enough resources to meet the demands of their job, they tend to perform better (Bakker & Costa, 2014). Therefore, employees of health-promoting leaders may perform better due to increased wellbeing brought on by the feeling that they have the resources to handle the demands of their job. By examining the mediating role of wellbeing, the current study was able to identify the route through which HPL affects job performance. In addition, this research expands on the geographical location of the sample to English-speaking Western Countries to enhance the external generalizability of existing literature.

Practical Implications

This current study also provides practical implications that can serve as a guide for leaders who wish to encourage employee wellbeing at the workplace. Leaders can apply these results to promote wellbeing among their employees. Prior research shows that HPL can be developed over time; therefore, all leaders have the potential to harness the benefits of HPL (Eriksson et al., 2010). For leaders to achieve superior job performance, it is essential to practice HPL that considers the employee’s wellbeing. Organizations can implement leadership development programs that help foster HPL behaviors. This is actively being implemented in four Norwegian industries where they focus on hands-on learning, accessible services, and supportive and inclusive feedback (Skarholt et al., 2016). Within these programs, leaders can be educated on the concept of HPL and discover ways to implement the behaviors into their current leadership style. As well, they can incorporate these behaviors into their hiring and promotion criteria. In the Johnson and Johnson case, they saved $250 million in healthcare costs and are seeing a return of $2.71 for every dollar spent due as a result of employee health initiatives (Quelch & Knoop, 2014). Similarly, a meta-analysis on the economic return of workplace health promotion found that employees who participated in workplace health promotion initiatives had 25% lower medical and absenteeism expenses than nonparticipants (Chapman, 2012). Based on successful companies with a culture of health promotion, Fabius et al. (2018) outline 10 categories that contribute to organizational health culture. A few of the categories include acquiring leadership support for the initiative, marketing to promote the value of health, establishing a multi-year health and wellness plan, a work environment promoting health such as a smoke-free campus, and having on-site health activities such as gyms.

Limitations and Future Research

One methodological limitation involves the self-report nature of the survey which is susceptible to social desirability or exaggerated responses biases that can pose a threat to the validity of the results (Lietz, 2010). For instance, the wellbeing scale demonstrated that it was moderately negatively skewed as the majority of people reported high levels of wellbeing. Future research could incorporate observations made by colleagues, supervisors, or researchers. This would help eliminate biases and provide researchers with a broader understanding of the concepts. Another limitation is the cross-sectional survey design. A mediational analysis was conducted to make causal inferences about the relationships in this study. However, because the cross-sectional design does not allow for the inference of temporality, the findings should be regarded with caution. Additionally, employee surveys conducted at one point in time have been critiqued for overlooking intricate factors that influence employees’ attitudes, behaviors, and relationships with their leader (Garrad & Hyland, 2020). Therefore, future research should consider longitudinal research designs or experimental designs where they train leaders on HPL to determine if that creates an increase in employee job performance.

The generalizability of the current study is another potential limitation. Although the study aimed to have a large sample across English-speaking Western countries, the final sample was relatively small (n=77) with the majority of the participants being located in Canada (92%). Therefore, the generalization of the study’s results to countries beyond Canada should be done with caution. Future research should continue to expand HPL research to additional geographical locations such as Asia since it tends to emphasize collective achievement rather than individual; making leaders in Asia focus on team success over individual performance (Mills, 2005). Finally, the characteristics of the leader are unknown. Supervisors were ranked on the HPL scale according to their followers’ perceptions of them. Thus, the intention of the leader is unknown, along with their attitudes toward health and wellbeing. Future research should consider the impact of HPL on follower performance from the leader’s perspective.

Conclusion

The current study’s results advance Industrial-Organizational psychology’s theoretical understanding and practice. From a theoretical standpoint, this research is the first to explore the connection between HPL and employee job performance. This theoretical contribution emphasizes the significance of valuing employee health and wellbeing, which enriches the present understanding of organizational effectiveness. Organizations can expect higher employee performance and increased organizational effectiveness if they place a high value on employee health. This research may encourage leadership coaches and organizational consultants to prioritize the health and wellbeing of employees in the organizations they work with.

Contact details for the corresponding author

Chelsea Coombes is a human resource and labour relations professional currently working in the healthcare sector. She has also worked in leadership and team development across a variety of industries, collaborating with healthcare professionals, first responders, tradespeople, and athletes. Chelsea holds a Bachelor’s degree in Psychology from Simon Fraser University and a Master’s degree in Industrial-Organizational Psychology from Adler University. Her research interests focus on improving workplace well-being, exploring strategies for enhancing employee engagement, and cultivating supportive environments that foster both personal and professional growth.

Ludmila Zhdanova is an Industrial-Organizational Psychologist with a Doctorate degree from Wayne State University. She is a faculty member at Kwantlen Polytechnic University, BC. Her primary research interests include cross-cultural adjustment processes, psychological climate, Congruence and Fit, and work-family conflict and balance. She utilizes her background in quantitative and qualitative methods to help companies in the areas of selection, validation, data analysis, and organizational surveys.

Rose Kajal is an undergraduate student at Kwantlen Polytechnic University. She is a research assistant for Dr. Zhdanova. She is an aspiring practitioner in the field of Clinical Psychology. Her primary research interests include psychopathological disorders; trauma; domestic violence; abuse; interventions for children and adolescents. She endeavours to create programs which will help abused children and youth from marginalized communities receive urgent care and support.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, Chelsea D. Coombes. The data are not publicly available due to Research Ethics Board’ approval restrictions.

Ethics Declarations

The manuscript is original. It has not been previously published, and it is not under concurrent consideration elsewhere.

This submission fully follows APA ethical guidelines and has received the approval of the Adler University (Vancouver) Research Ethics Board.