Healthcare service delivery in British Columbia (BC) is under pressure to provide high quality care while managing limited resources efficiently and effectively, the current model being inadequate to meet future demands.

In response, the BC Ministry of Health has mandated the Provincial Health Services Authority (PHSA) with transforming the delivery of service. With this mandate, PHSA, and the newly formed Provincial Laboratory Medicine Services (PLMS) under it, are poised to implement transformational change to laboratory service delivery.

Even with a viable plan, support from the organization’s members is vital for achieving change successfully (Hiatt & Creasey, 2012). Becoming ready for change depends on the readiness and support of organizational members. Change agents can not force readiness, but they can influence it by actively fostering supportive environments (Agote et al., 2016).

This researcher conducted a qualitative action research study using an action research engagement method (Rowe et al., 2013) to examine the change readiness of health authority laboratory leaders toward the pending change.

The study assessed their current readiness, identified enablers, and developed recommendations for forming a cohesive provincial system. From these discussions, key themes emerged, which led to several recommendations. Trust emerged as an underlying theme in all aspects of health authority laboratory leaders’ readiness for change. By instilling trust throughout the organization, the new PLMS builds change readiness into its culture and character, enabling it to weather future planned and emergent change environments and ensure its long-term sustainability (Vakola, 2013).

These findings have relevance to organizations beyond the laboratory service. Additionally, this work contributes to the body of knowledge on change readiness by positing that high levels of trust are necessary to prepare an organization for both planned and emergent transformational organizational change.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The researcher examined the constructs of change readiness at the individual and collective levels, the enablers for successfully facilitating change readiness at both levels, and the development of a novel mindset conducive to creating a new system-level organizational identity. The ultimate goal of the PLMS organizational change initiative is to form a new entity that is truly transformative, innovative, and cooperative. Building engagement with the change initiative early sets a solid foundation for meeting these long-term challenges. Recognizing that change readiness is a potent predictor of future change initiative success, this literature review looks specifically at change management concepts related to change readiness and transformational organizational change.

Attributes of Change Readiness

Change Readiness Constructs

Holt, Armenakis, Feild, and Harris (2007) described change readiness as follows: A comprehensive attitude that is influenced simultaneously by the content (i.e., what is being changed), the process (i.e., how the change is being implemented), the context (i.e., circumstances under which the change is occurring), and the individuals involved (i.e., characteristics of those being asked to change) (p. 235). What individuals think and how they feel about a change initiative can be qualitatively different (Oreg et al., 2011). Peccei et al. (2011) suggested that emotional attachment to the change initiative is a vital and necessary contributor toward change readiness. Preparing individuals psychologically and emotionally for change facilitates their ability to progress to the point where they would act on their thoughts, feelings, and beliefs.

Change Readiness–Change Resistance Spectrum

Change resistance is often discussed in the literature as the opposite of change readiness (Self & Schraeder, 2009). However, scholars have not attempted to develop a consensus definition for change resistance, in part because it is considered a mostly negative label assigned to the change recipient by the change agent (R. Thomas & Hardy, 2011).

Resistance to change should not be construed as wholly negative. Frahm and Brown (2007) posited that change resistance could be both negative and positive. From a systems perspective, change resistance could simply indicate a lack of sufficient applied organizational energy to overcome the inertia of staying the same. As the forces for change increase, resistance to change necessarily diminishes (Burnes, 2015).

Scholars have described ambivalence as an attribute between change readiness and change resistance, as the stakeholder experiences conflicting positive and negative attitudes simultaneously toward the change initiative (Grimolizzi-Jensen, 2017). Accordingly, ambivalence was not used in this study as it represents any of the many opposing attitudes that fall within the spectrum. As a more neutral term than ambivalence, non-commitment was used in this study to indicate the midpoint in the continuum. Each of the chosen attributes has emotional and cognitive components that correspond to the degree of intensity and intentionality of the attitude across a spectrum. Figure 1 illustrates how cognitions, emotions, and intentions lead to changes in behaviors. The more overt, observable intentions and behaviors are visible at the extremes, with less intentional thoughts and feelings manifesting toward the center.

Becoming ready for change follows the change recipient’s decision-making process throughout the change event in response to external and internal inputs (Stevens, 2013), enabling the individuals to reach a point at which they are fully committed to supporting and promoting the change initiative.

Communication About the Plan

The first way to enable change readiness is through high-quality information about the change plan. Gilley, McMillan, and Gilley (2009) linked the quality of change agents’ communication to higher levels of change readiness in the change recipients. Within the context of this change initiative, an inadequate governance structure with corresponding lack of authority to implement decisions and an unsustainable and inequitable funding model are the sources of much of the skepticism and doubt about this change initiative.

In addition to their cognitive responses to the change initiative, change recipients respond emotionally to external change interventions (Elfenbein, 2007). Fears over altered organizational relationships and concern over how the change will personally impact their job duties, roles, and responsibilities all negatively affect an individual’s change readiness (Self & Schraeder, 2009).

Trust

Colquitt, Baer, Long, and Halvorsen-Ganepola (2014) described trust as a relational construct between individuals whereby the fulfillment of psychological contracts between them creates a willingness to engage in beneficial behaviors. Devos et al. (2007) found that higher levels of trust in the leader were closely related to increased openness to change. According to Elving (2005), “Trust guides the actions of individuals in ambiguous situations” (p. 133). Without trust, change recipients are more likely to be critical of the information or justification they receive in the context of organizational change" (Allen et al., 2007, p. 191).

Collective Engagement

While change recipients are undergoing the process of individual sense-making about the change plan, they are also interacting with others in the organization to collectively make sense of the change. In this change management process, the most important dyad is between the change agent and the change recipient (Maslyn & Uhl-Bien, 2001).

Engaging in discourse enables mutual meaning-making, allowing the two to align with the same shared purpose (Bushe & Marshak, 2016). A shared vision is collectively developed, inspires excitement, and motivates the members of the organization to actively commit to the organization’s success (Kouzes & Posner, 2012). Participation becomes even more important as the degree of impact of the change on the individual’s work increases (Burnes, 2015). Thomas and Hardy (2011) found that participation yielded the added benefit of promoting a non-adversarial relationship between the change agent and change recipient.

Transformational Organization Change

Transformational leaders have the ability to share ownership and distribute leadership among their followers, thereby developing the organizational capacity to manage complex issues (Gilpin-Jackson, 2015). Empowered followers are more likely to partner with others and take responsibility for the future success of the organization. Building a culture of transformational organizational change shifts the focus from managing change to managing organizational relationships (Burns, 2001). The transformational leader is fundamentally responsible for guiding followers to adopt a new way of thinking and acting.

Organizational Identity

The second powerful facilitator of organizational change is the formation of an identifiable organizational identity. Elving (2005) found that sharing details about the change plan can begin the formation of a sense of community among organizational members at the macro level. By recognizing and honoring past and future identities, recipients of change can begin psychologically separating themselves from their old identity as they form a sense of connectedness to one another.

METHODOLOGY

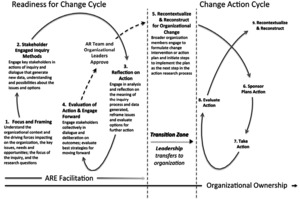

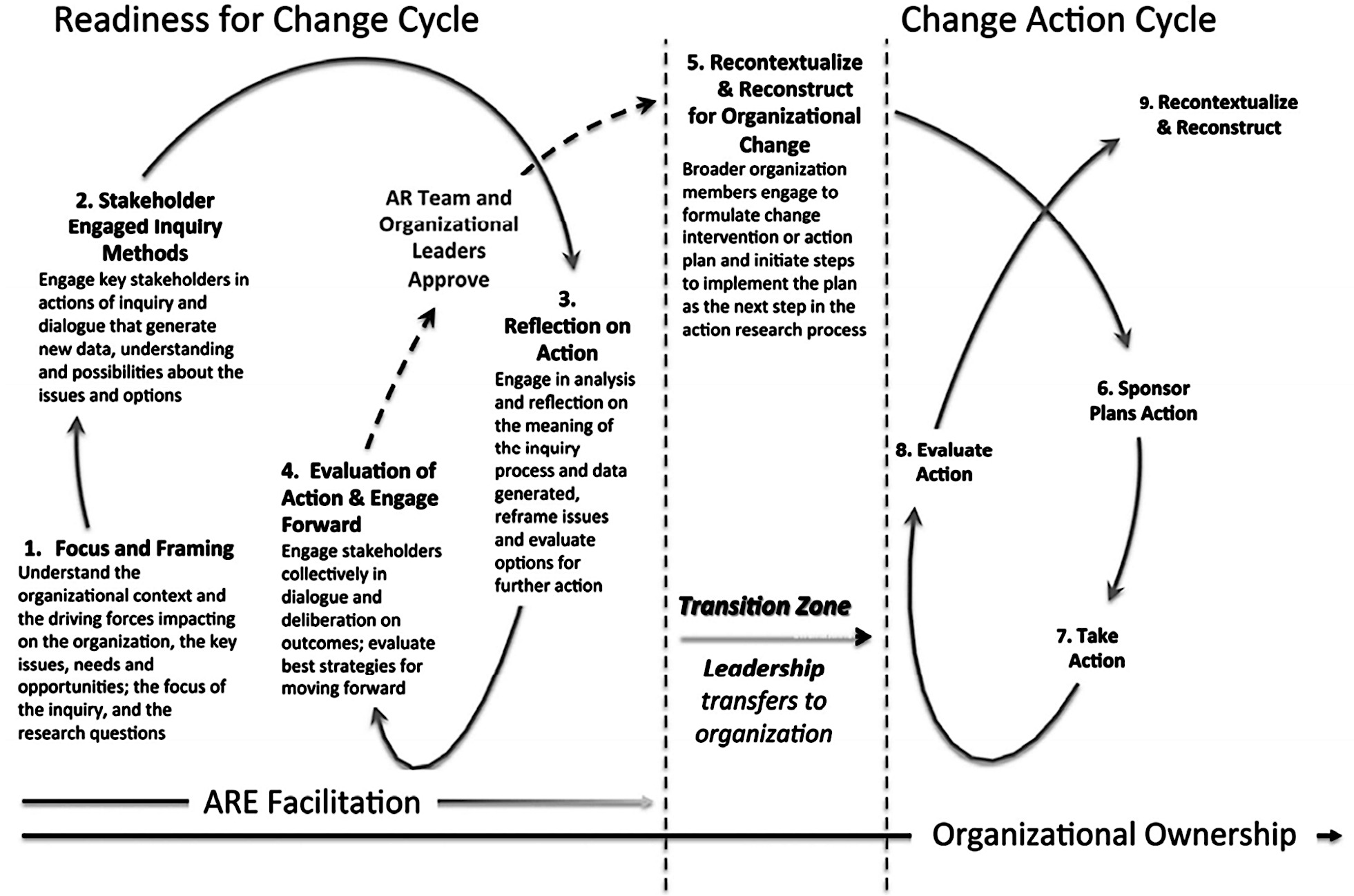

This chapter describes the foundational Action Research (AR) methodology and the Action Research Engagement (ARE) approach, as described by Rowe et al. (2013). The specific data collection and data analysis methods used during this project, and a detailed description of how the study was conducted, giving specific attention to how the research met acceptable quality and validity requirements to ensure the results are supported by solid evidence and facts.

Action Research Methodology

With AR, all participants experience the inquiry and analysis together as they collaboratively design practical solutions to a real-world issue, with enhancement of the quality of those relationships as an additional outcome. Through the development of the skill of personal reflection throughout the course of the project, AR methodology facilitates the participants’ ability to change how they think about issues, which they can use to address future challenges, acknowledging that once the research is done, the learning and adapting process continues (Coghlan & Brannick, 2014).

This method incorporates practical application as a critical component of the methodology so that it does not become simply an academic endeavor, but rather results in positive change for the organization and creates useful knowledge (Bradbury-Huang, 2010). Nonetheless, AR is not without its drawbacks. As an active co-participant embedded in the process of discovery and relationship-building, the researcher loses the arm’s-length objectivity necessary to interpret the data and determine the findings, conclusions, and recommendations without the strong influence of personal bias (Coghlan, 2013). Being one of the more subjective qualitative methodologies, the propensity for personal bias often blinds the researcher to alternative interpretations.

Action Research Engagement Approach

The ARE method met several criteria for successfully discovering how to effectively increase the change readiness of this select group of participants in anticipation of significant organizational change. The ARE model specifically investigates the change readiness of key stakeholders affected by the change initiative. It was useful for uncovering the underlying attitudes of the participants, identifying the barriers to engagement, and developing strategies to enable them to participate collaboratively in forming a new organizational identity.

Second, transformational change to how laboratory service is delivered may take years to accomplish, so restricting the scope of the project to understanding health authority laboratory leaders’ state of change readiness in the early stages of the change initiative may provide more actionable metrics. The ARE model (see Figure 2) incorporates the action-oriented, participatory approach of “planning, acting, observing, and reflecting” (Stringer, 2013, p. 9) into its four phases, which form the first iterative cycle of the ARE process.

The objectives of this research were to answer the inquiry questions and create new knowledge, co-create learning, and build relationships amongst the group members to become a highly functional team, and, finally, to stimulate personal growth and change within each participant.

Data Collection Methods

This study utilized two main data collection methods: individual interviews and a focus group teleconference.

The first data collection method sought to capture underlying emotions, attitudes, and beliefs toward this organizational change. Individual interviews have several advantages over quantitative methods. Personal interviews provide each participant with the opportunity to engage more fully in their own individual self-discovery of their current level of understanding, thoughts, feelings, beliefs, and perceptions regarding the consolidation plan (Rafferty et al., 2013). Furthermore, semi-structured interview questions have the advantage of allowing individuals the opportunity to lead the conversation into areas they consider most important, while the interviewer maintains focus on the research objectives (Taylor et al., 2015).

Individual Interviews

The first data collection method sought to capture underlying emotions, attitudes, and beliefs toward this organizational change. Individual interviews have several advantages over a quantitative method, such as a survey. Personal interviews allow each participant the opportunity to be more fully involved in individual self-discovery of his or her own current level of understanding, thoughts, feelings, beliefs, and perceptions regarding the consolidation plan. In-person interviews also afford the researcher the opportunity to promote an informal, psychologically safe environment for sharing feelings about the change initiative and to build rapport with interviewees that would be conducive to open, honest, high-quality responses

The interview questions were based on the work done in two relevant studies. Devos et al. (2007) evaluated change readiness by assessing the change recipient’s level of trust in the change agents and history with previous change initiatives, in this case, previous laboratory reform efforts. Holt et al. (2007) developed several other criteria, which included the change recipient’s belief that the change was necessary, the change plan as designed could achieve its objectives, the initiative was the right approach to change, and that the leaders have the ability to accomplish their change objectives. Holt et al. (2007) also included the change recipient’s dispositional attitude toward change as a relevant measurement. The interview questions were designed to reveal the individual’s thoughts and feelings for each of these parameters.

Focus Group Method

Informal settings are conducive for individuals to present differing or conflicting perspectives, while also encouraging connectedness among participants. A teleconferencing method offered the major advantage of being able to schedule the 1-hour meeting at a time convenient for all participants (Schneider et al., 2002).

Project Participants

The total population of individuals whose perspectives were relevant to this study was small, so the “purposive sampling” approach described by Etikan, Musa, & Alkassim (2016, p. 1) was selected to invite all 14 regional or provincial medical and operational leaders from each of the public health authority laboratory medicine departments in BC, as they fell within the scope of this project.

Four interview team members, including the researcher, conducted a pilot test of the interview questions, with one member being in a leadership position from one of the member laboratories.

Study Conduct

This study collected data from individual interviews with each of the participants to generate the first data set. Following Holt et al.'s (2007) recommendations, the interview data were analyzed to identify both a priori (deductive) themes, which were directly addressed in the interview questions, and emergent (inductive) themes, which emerged through data analysis. Each interview question was based on input from IT members to ensure the answers directly addressed the research question and yielded the desired information.

The researcher emailed each target participant with the invitation to participate in an individual interview as the body of the email. Upon receipt of the signed consent, a suitable time and place were scheduled to conduct the interview. Individual 1-hour interviews were conducted either in-person or via teleconference, spanning a 2-week period. Semi-structured interview questions were framed to capture the individual’s demographic attributes, attitudes toward past change initiatives, baseline attitude toward change, attitudes toward the current change plan, faith in the organization, and the Senior Leaders’ ability to accomplish the plan, and the impact the change might have on their many healthcare partner relationships.

Data Analysis

Following Thomas’s (2003) advice, a qualitative data analysis approach was applied to deductively answer the research questions and inductively draw deeper meaning from the data through the discovery of emergent themes. The condensed transcripts, representing the data corpus, were emailed to the appropriate participant for review as a member check to ensure the information accurately captured their perspective.

Research Quality and Validity

The researcher applied both deductive and inductive thematic analysis. Transcripts were condensed and coded for change-related attitudes. A second reviewer independently coded the data. The focus group data underwent constant comparison analysis to identify consensus and divergent views. A follow-up survey validated the findings.

Ethical Implications

As the research project involved humans as the main source of data, particular attention was paid to three core ethical principles: respect for persons, concern for welfare, and justice. The objectives and conduct of the study were thoroughly outlined, clearly informing each potential participant that taking part in the inquiry was voluntary and describing the process to decline or withdraw consent at any time without any harm.

FINDINGS

Participation in the individual interviews was 71% (10 of 14 possible participants) and 43% for the focus group (six of 14). The high participation rate for both data collection methods, combined with the balanced distribution of each category across methods, allowed for a comprehensive understanding of the overall attitudes, concerns, and suggestions of these primary change recipients, thereby increasing confidence in the validity of the findings and conclusions.

This inquiry revealed that change recipients were currently at a stage at which they neither endorsed nor actively opposed the change. Numerous factors contribute to their current attitude, which, when adequately addressed, could influence them to more actively endorse the change initiative. Their endorsement is pivotal to making the change initiative successful and sustainable, as they will be the change champions to extend change readiness throughout the rest of their organizations.

Collectively, participants’ general dispositional attitudes toward organizational change were overwhelmingly positive. However, an assessment of the range of attributes expressed during the interviews revealed that all participants expressed some degree of conflicting positive and negative attitudes toward the change initiative. Several participants exhibited high levels of skepticism, drawing on their historical knowledge of past laboratory reform efforts. At the same time, many participants found reason to be optimistic that real change was possible this time.

Several participants were disappointed with the delay in action. Perceived lack of communication further contributed to the loss of engagement. High levels of skepticism, doubt, and ambivalence show the degree of personal apprehension regarding the change. Concurrently, their own natural optimism toward organizational change was gradually being eroded. The preponderance of anxiety and fears indicates poor emotional engagement.

During periods without significant information sharing, health authority laboratory leaders engaged in individual and peer sense-making, which the literature showed generally exacerbates negative perceptions about the change (Elving, 2005). They suggested that high-quality, consistent messaging would build and sustain positive levels of engagement.

The participants’ varied perspectives revealed the numerous competing tensions that prevented them from forming a cohesive identity. They were looking to the future, but at the same time, it was unclear if they were all looking in the same direction. Transformational change is stressful, especially for those who experience the greatest impacts on their current operational duties (Anderson & Ackerman Anderson, 2011). The underlying theme throughout all of these findings was the importance of trust at every level. Building trust requires real, authentic relationships. Building trust into the culture and character of the organization ensures that change readiness is embedded at all levels to handle any future planned and emergent changes.

Scope and Limitations of the Inquiry

As a qualitative project, the findings and conclusions depend on the specific individuals involved and the context of their responses to the study questions. This research was conducted over a 2-month period during a time when organizational change was highly anticipated, but no observable progress was apparent at the level of these laboratory leaders, yet the situation remained dynamic. Given that the data showed engagement by these key leaders was actively eroding over time, a different timeframe might have shown a much different picture.

This study notably did not include the private laboratory service provider leaders who will also coordinate their services with the PLMS, but in a different capacity, with different roles and responsibilities, nor did it engage the change agents along with the change recipients in the focus group discussions.

FUTURE DIRECTION

Change readiness has been demonstrated to be a significant predictor of the eventual degree of success of any change project (Rowe et al., 2013). Given the high stakes of this large system transformation, this report is the culmination of my partnership with the PLMS leaders to examine health authority laboratory leaders’ current state of change readiness, discover the barriers they encountered that have hampered them from being readier for change, and design some strategies for developing a system-level mindset as a single laboratory service delivery stream.

Building Change Readiness by Creating Trust in the Plan

Access to high-quality information facilitates the individual’s internal decision-making process positively, leading to greater readiness for change in response to change events (Stevens, 2013). To address these concerns, the laboratory leaders suggested that they receive consistent messaging delivered to everyone simultaneously, preparing them to accept and embrace the organizational change plan as they work together to design the process and facilitate the formation of healthy working relationships.

Increasing Change Readiness by Developing Trust in the Process

Patvardhan et al. (2015) advise organizations to form cohesive groups around issues of common interest rather than functional lines. Changing how these groups meet would also help facilitate more cohesiveness among the groups. Considering that most meetings are conducted by teleconference, effort should be made to ensure that those not in the room are actively involved in the conversation.

Strengthening Trust and Improving the Quality of Relationships Throughout the Organization

Strong relationships are critical for organizations to achieve transformational change. They can build change readiness by developing a personal relationship with each health authority laboratory leader.

Transformational change puts greater stress on the individuals most impacted by the change. Group interactions will have to be more functional, respectful, and open. Bruckman (2008) noted that trust was a key ingredient for group cohesion. He suggested they engage in “teambuilding, trust building, and open, honest communication prior to the introduction of the change” (p. 215). A sense of cohesiveness can begin to emerge when groups form around shared problems to arrive at mutually determined solutions (Patvardhan et al., 2015). Healthy relationships depend on respectful interactions, constructive dialogue, and openness to others’ perspectives in a safe environment. Effective teams take advantage of developing a group charter to clearly define the expectations of each member. Employing any or all of these suggestions can enhance the functionality of leaders’ working relationships as they explore new ways to interact in a safe and trusting environment.

Successful organizational change relies on the willingness of the organization’s members to support the new initiative. Although this study is highly context-specific, there are lessons that can contribute to the larger scholarly audience regarding change readiness. Through this study, the key stakeholders had the opportunity to collectively explore the common themes that limited their ability to endorse the change initiative and to develop recommendations. These findings and conclusions could inform similar organizations undergoing a metalevel, system-wide transformation.

Organizational Implications

Incorporating change readiness into the character and culture of the organization sets a complex organization on a trajectory for being nimble, responsive, and sustainable when faced with both planned and unplanned future changes. While the context of this change is specific to this group, the premise presented here could be applied to any group undertaking transformational organizational change.

CONCLUSION

This study investigated the state of change readiness among a cohort of laboratory leaders who are undergoing a significant transformation in their operational structure within their regional health authority as they become key members of a new system-wide organization. The learnings discovered in collaboration with health authority laboratory leaders during this change could be instructional for others as they embark on similar seismic organizational changes. Most leaders are inherently optimistic about change, recognizing that it is a mechanism for ongoing improvement. It also serves as a cautionary tale, highlighting that known barriers must still be addressed for recipients of the change to have faith that the change effort can ultimately be successful. To further encourage change recipients to engage with the change effort, the laboratory leaders identified a need for regular information updates. In the event there are no details to share, all they ask is that the change agents provide periodic updates that are honest and transparent. Finally, when a change requires a new organization to form, efforts to build trust among all stakeholders help them work collectively to establish a new organizational identity and discover new ways of working together to achieve a purpose larger than they could achieve on their own.

With the people of the organization being a tipping point for success, building change readiness among these key individuals could make all the difference. As this study has shown, change readiness is a true indicator of the level of trust within the entire organization. Change readiness begins when the individuals trust that the plan and the process are something they can endorse. It grows as trust forms in the personal relationships between all participants and enables them to work effectively on complex, challenging, and contentious issues. It spreads as the organizational members sense the opportunities that their collective efforts can achieve when they work toward one common purpose of doing what is best for all involved.

Many factors contribute to achieving all the objectives of a change initiative. Building commitment of the key leaders into the change plan ensures that the human component is on a trajectory toward successfully achieving all the change objectives for forming a single, consolidated, provincially coordinated service delivery stream.