Introduction

People engaged in transdisciplinary (TD) work assume tremendous levels of responsibility as they grapple with complex wicked problems whose lack of solution yields intractable consequences (e.g., climate change, unsustainability, violence and injustice, threats to biodiversity, poverty and income inequality, and social inequities). “Complex wicked problems are context and situation unique, hard to define and very unpredictable. Many disparate stakeholders (with varying points of view, perspectives, interests, resources and power) are vying for a voice in their problematisation and resolution” (McGregor, 2024, p. 5).

These wicked problems are messy, vicious, fierce, aggressive, intolerably bad, and distressingly severe (McGregor, 2024). The more people do, the worse things get; yet something must be done because the stakes are so high. Völker (2020) called for transdisciplinary knowledge producers and co-creators to use “responsible approaches to solving contemporary problems” (p. 47) where “facts are uncertain, values in dispute, stakes are high, and decisions urgent” (Funtowicz & Ravetz, 1992, p. 252).

These high stakes trigger responsibility and accountability. Responsibility (Latin respondēre, ‘to offer in return’) means accountable or answerable for one’s actions (Harper, 2025) in particular those “within one’s sphere of influence” (Franzini Tibaldeo, 2024, p. 300). This sphere, impacted through relationships and advocacy, differs from a sphere of concern, which cannot be directly influenced but is affected by ripple effects (Thorneycroft, 2023). That is, actions do not exist in insolation. “Instead, they have a cascading and interconnected impact … beyond their initial occurrence … to further-removed people and areas” (Arena, 2023, para. 2).

The Zurich approach to transdisciplinarity (so named for the 2001 conference where it was formulated) (Klein et al., 2001) actually presumes that any knowledge co-generated at the science, society, and technology interface must be socially accountable, meaning its diverse and myriad creators must assume responsibility for and justify its creation (i.e., provide reasons). Socially accountable knowledge is created when (a) there is full awareness of how different societal stakeholders are affected by the knowledge and (b) those involved can justify it to them and the context where it will be applied (Klein et al., 2001; Völker, 2020).

This paper explored the neologism transdisciplinary responsibility. A neologism is a newly coined term that is not widely used but has the potential to become mainstream (Anderson, 2006). “Neologisms may have an important, yet underrated and not sufficiently investigated potential to influence the speed of social change” (Zella et al., 2025, p. 1). By introducing “new ways of thinking, neologisms influence collective thought processes” (Storjohann, 2025, p. 318). Insights into what constitutes transdisciplinary responsibility should inform and influence the thought processes of future transdisciplinary group work on complex, wicked problems — especially within management circles.

Method

This is a qualitative, exploratory study, which is useful when researchers need explanations and better understandings of a phenomenon, to clarify or confirm how a concept has been conceptualized or defined, and to affirm or refute the need for further in-depth research. A literature review, used herein, is an accepted method for exploratory research, as analysis of existing literature can reveal leads for further investigation (Swaraj, 2019; Yin, 1994) and inform the conceptualization of phenomena (McGregor, 2018).

Data Collection and Analysis

A July 2025 Google Scholar search (results printed off for posterity’s sake and revisited in September) for the exact phrase ‘transdisciplinary responsibility’ yielded only 16 distinct artifacts from 14 different sources. Found artifacts and emergent data were analyzed using a combination of content analysis (coding for one term) and descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages). Once identified, each artifact was searched using the CTRL Find function to identify the exact presence of transdisciplinary responsibility and its associated context. Direct quotes were harvested and profiled in a table, which itself underwent a secondary analysis.

Sample Frame

Half (50%, n = 8) of the artifacts were from the last two years (2024–2025) with the rest published between 2003–2016 inclusive. Most (63%, n = 5) of the former were directly from or related to two edited books, one about (a) transdisciplinary thinking and acting (Schüz, 2025a) and the other about (b) the business sector’s transformative role in promoting well-being through sustainable practices including a transdisciplinary lens (Mühlböck, 2025). No artifacts were found between 2017–2023, which is an inexplicable seven-year gap given the exponential rise in research about transdisciplinarity (Harris et al., 2024).

Within the last two years, aside from two books, three disciplines have published journal articles mentioning transdisciplinary responsibility: urban planning, business, and chemistry. Research between 2003–2016 was published exclusively in scholarly journals (no books) but by different disciplines: computer science (CS), medicine, engineering, sociology, education, and occupational sciences. This amounts to only nine disciplines mentioning transdisciplinary responsibility out of 8,000+ academic disciplines worldwide (see Nicolescu, 2014).

Artifacts were found in books (44%), journals (31%), conference proceedings (13%), the Social Science Research Network (SSRN) repository (6%) and institutional policy briefs (6%). The inclusion of this neologism in edited books (both 2025) is significant, as such collections often introduce cutting-edge, innovative conceptualizations intimating that transdisciplinary responsibility fits that bill. “Edited books continue to play a vital role in shaping the intellectual discourse of our time” (MDPI Books, 2023, para. 10) as do neologisms (Storjohann, 2025).

Findings and Discussion

Search results (see Table 1) suggest that transdisciplinary responsibility was not a popular search term. People are not yet tying responsibility with transdisciplinarity, which is a powerful initial finding in its own right. Combining the two terms is a somewhat recent innovation.

In another revealing finding, no authors defined or conceptualized transdisciplinary responsibility; instead, all but one used it in one sentence (see Table 1), and none provided further elaboration. That said, the undefined term was used in myriad contexts dealing with some aspect of complex, wicked problems: managing complexity and polycrises, urban planning, business practices using artificial intelligence (AI), lithium extraction resource management, pain management, occupational therapy, curricular reform in areas such as computer science and engineering, and higher education scholar-practitioners’ responsibility to students. Evidence of its usage is now presented and organized by the last two years followed by artifacts published during an earlier 14-year time frame (2003–2016 inclusive).

Transdisciplinary Responsibility 2024–2025

Schüz (2025a) exemplarily noted that “transdisciplinary responsibility is in high demand [when] gaining a better understanding of our world and addressing complex problems. After all, the fundamental power of man [sic] to reshape the world with the help of his knowledge forces him to take into account the far-reaching consequences for the whole and to shape it in a way that is beneficial to all forms of life” (Research Gate Abstract).

Schüz (2025c) further observed that our inclination to dominate nature “improved our living conditions unimaginably [but] at the same time almost irrevocably destroyed important foundations of life [that] demands a transdisciplinary responsibility for the consequences” (p. ix). And he held that “a holistic model of transdisciplinarity serves as orientation for the necessary thinking and acting, which respects the diversity of possible constructions of reality, but at the same time ties it back in the cognition and ethical demand of a universal (transdisciplinary) responsibility” (Schüz, 2025b, p. 5).

Mühlböck and Schmidpeter (2025a) explained that transdisciplinarity arose as a way to deal with the world’s increased complexity. It offers a “plurality and abundance of insight generation [that] contributes to an ever-expanding understanding of how the world works and how our actions might influence it. [Any co-created, integrated knowledge should take into account] transdisciplinary responsibility” (p. 332). They believed that transdisciplinary responsibility would foster the sustainable transformation of humankind, thus intimating that transdisciplinary irresponsibility could compromise humanity’s future. “A contextual knowledge universe for the concept of well-being emerges and integrates and thus … ethical knowledge in the sense of ‘transdisciplinary responsibility’ [must] be again taken into account” (p. 333).

In addition to integration and differentiation (i.e., diversity and divergence), Mühlböck and Schmidpeter (2025b) claimed, in a different book chapter, that interdependence and interrelatedness are transdisciplinary fundamentals that trigger “transdisciplinary responsibility” (p. 95) (i.e., full accounting of and justifications for decisions and outcomes in a transparent manner). Individual, society, and the planet are all one — what happens to one affects the others. Interconnected means there is a link. Interrelated means people are aware of the link and can see potentials. Interdependent means the actualized link is mutually beneficial (i.e., both parties gain something of value) (Stevenson, 2011). People, especially managers, are remiss if they disregard the responsibilities inherently arising from transdisciplinary connections (Mühlböck & Schmidpeter, 2025a, 2025b).

Bonelli and Gamba (2024) envisioned “a transdisciplinary responsibility that critically questions the universal vision of a future-oriented battery-ion age” (pp. 6–7) (e.g., consumer electronics, laptops, cellular phones, and electric cars). They proposed an alliance between chemistry and anthropological perspectives on lithium extraction to better “empower people to think and act together, facilitating connections among divergent concerns” (p. 20). Embracing transdisciplinary responsibility would help people “challenge linear illusions of progress while embracing the complexities of our planetary present and past” (Abstract).

Erbacher et al. (2024) observed that “the potential impact of AI not only on the labor market but also on society highlights the need for transdisciplinary responsibility beyond company boundaries” (p. 12). The responsible introduction of AI into business management practices depends on collaboration between AI and humans rather than letting AI innovate independently. As social actors, corporations that use AI to generate future-proof solutions for their business must responsibly shape future technology. This demands transdisciplinary responsibility for ripple effects of in-house management decisions on the wider world.

Urban infrastructures comprise social systems (e.g., education, health, recreation, culture, and green and blue space) as well as transportation, energy, wastewater, and information and communication systems. The inherent diversity, density, reciprocity, interconnectedness, and complexity of urban infrastructures mean that urban planning decisions pursuant to climate change and climate adaptation must be filtered through “a transdisciplinary responsibility” lens (Müller & Scheer, 2025, p. 6). Future urban resiliency and climate sustainability are compromised when actors ignore the ripple effect of their actions pursuant to urban infrastructure planning; that is, if they ignore their transdisciplinary responsibility (Müller & Scheer, 2025).

Transdisciplinary Responsibility 2003–2016

Hartenstein (2006a, Abstract) argued that “it is time for a curricular upgrade. Current computer science curricula do not sufficiently meet their transdisciplinary responsibility” because they lack a transdisciplinary perspective. CS curricula eschewed learnings from other disciplines (e.g., system architecture) and from computer startup companies (e.g., software, and configware), and they failed to combat fragmentation with a key example being application-specific computing algorithms and methodologies (Hartenstein, 2006a, 2006b). Hartenstein and Kaiserslautern further lamented that then-recent CS curricular “recommendations completely fail to accept the transdisciplinary responsibility of computer science to combat the fragmentation… This is criminal” (2007, p. 488).

Schechter (2008) recounted the failure of a pain management strategy called the Ouchless Place. Because “pain control is a transdisciplinary responsibility, no one person or discipline could be in charge of the Ouchless Place” (p. S156). She meant that pain control is the responsibility of many different actors. This transdisciplinarity responsibility — leading to more humane care — requires a focus on centralized planning augmented with recognized authority figures, efficacy, integrated diverse knowledge, and collaboration.

Guevara-Perez (2012) lamented that architecture, urban planning, and engineering courses tended to teach “conceptual knowledge” without concern for the context within which the knowledge would be applied. They failed “to teach the transdisciplinary responsibility that these professionals have in the creation or mitigation of the seismic risk of contemporary cities” (p. 163). Also, because hard-to-comprehend divergent, disciplinary conceptual knowledge makes it hard to understand each other, people cannot readily assume joint transdisciplinary responsibility.

Strydom (2015) claimed that “cognitively enriched social theory and sociology [have a] transdisciplinary responsibility” (p. 246) when it comes to the nature-nurture debate. Sociology can best assume this responsibility by developing transdisciplinary knowledge, which combines (a) objective nature (i.e., empirical, quantitative sciences) with (b) subjective and critical nurture (i.e., transformational societal processes, institutions, and cultural forms).

Beaudin and Berends (2016) advocated for a transdisciplinary approach in higher education because it provides learners with a space to imagine new solutions reflecting and affecting social, cultural, and ontological change. They argued that scholar-practitioners (i.e., bridge builders who both teach and study teaching) were “uniquely positioned to model this collective and transdisciplinary responsibility for student learning and development [especially if they orient learners to transdisciplinary] liminal spaces between and beyond disciplines [where] the potentiality for transformation [can be found]” (p. 104). When people stand on the liminal threshold between what they knew and what they are being challenged to learn, established boundaries blur, and new possibilities emerge (Horvath et al., 2009).

Regarding connections between the way authors used the term, cursory analysis suggests that they either (a) stated that transdisciplinary responsibility is in high demand due to the world’s complexity, (b) lamented that people were not engaging in it when they should be, (c) identified instances (triggers) that demand transdisciplinary responsibility be taken into account or (d) described what would happen if people were transdisciplinarily responsible.

In a novel twist, Barnes et al. (2003) acknowledged that practitioners had assumed transdisciplinary responsibility rather than eschewed it. “Transdisciplinary responsibility was reported for occupational therapy-related interventions, as the majority of occupational therapists and teaching staff shared in the provision of… interventions. Team collaboration was felt to be important” (p. 341) with some people hesitating to contribute unless the collection of diverse practitioners collaborated to better ensure responsible outcomes.

Conceptualizing Transdisciplinary Responsibility

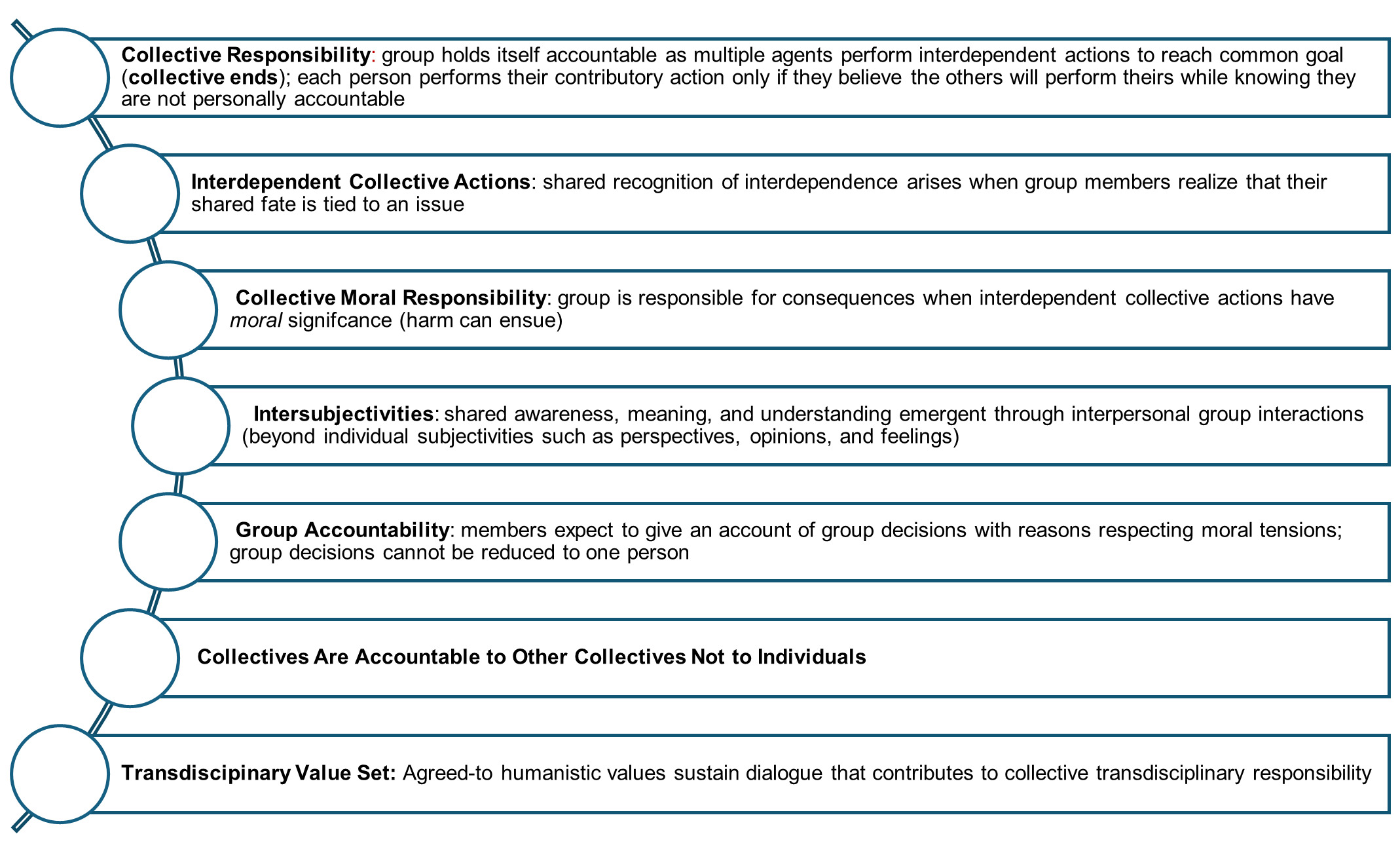

A key finding was that authors did not define or conceptualize transdisciplinary responsibility nor did they engage with how responsibility changes when it is described as transdisciplinary. This section elaborates an inaugural conceptualization of transdisciplinary responsibility starting with the fact that, with any responsibility, people are charged with executing a task, duty, or obligation with the expectation of providing a full accounting of the reasons behind their decisions and justifying any consequences from their actions. Accountability refers to owning the results of any actions taken to execute a responsibility. If the decision is unjustifiable, meaning the person cannot give a full accounting of the reasons for their actions, they have been irresponsible; that is, they have failed to fulfil their duty (McGregor, 2017). This basic reasoning holds for transdisciplinary responsibility with the following text tendering a discussion of how it might be conceptualized along seven dimensions (see Figure 1).

Collective Responsibility

Upon reflection, it seems that transdisciplinarity triggers collective responsibility rather than individual responsibility, which has precedence in our society (Bakeeva & Biricheva, 2021). Transdisciplinary work involves collectives of diverse actors with divergent interests, viewpoints, values, and so on. No one person can be held accountable in these instances. The group has to hold itself accountable. Unfortunately, “the actual phenomenon of collective responsibility remains insufficiently conceptualized” (Bakeeva & Biricheva, 2021, p. 42) as does transdisciplinary responsibility (i.e., no authors in the Google Scholar search defined the term).

For a collective to be a collective that can be held responsible, (a) all members must have the “collective end as the end” (Miller, 2006, p. 180); and (b) all member actions must be interdependent; that is, each person performs their contributory action only if they believe the others will perform theirs. A collective end is the shared goal, purpose, objective, or consequence that motivates or results from collective actions and responsibilities. Collective ends drive the group’s collective action – what they are striving for (Miller, 2020). Thus, with collective responsibility (and by association transdisciplinary responsibility), “there is a collective end and there is interdependence of action… The full set of acts [is] the means by which the collective end [is] realized” (Miller, 2006, p. 180).

Interdependent Collective Actions

Regarding interdependent collective actions, Miller (2001) distinguished among individual, corporate/national, and joint activities. Individual action is one person acting alone. Corporate or national actions are large separate entities acting alone. However, joint or shared actions occur when “two or more agents perform interdependent actions … to realize some common goal” (p. 65). In interdependent individual actions, people rely on each other to act, and their actions affect one another. But interdependent “collective action emerges from shared recognition of interdependence … when groups of people realize their shared fate is tied to an issue” (Cousins & Zale, 2025, para. 16). This shared fate is the crux of complex, wicked problems (Funtowicz & Ravetz, 1992).

Collective Moral Responsibility

Furthermore, collective responsibility tends to be about morality (i.e., harm arising from an action or decision) instead of causality, which is associated with individual responsibility (Giubilini & Levy, 2018; Miller, 2020; Smiley, 2022). Miller’s (2001) “collective moral responsibility” (p. 68) concept is, thus, useful here. Within the collective, “each agent is individually morally responsible but conditionally on the others being individually morally responsible; there is interdependence in respect of moral responsibility” (p. 68). “Roughly speaking, if a set of agents is collectively naturally responsible for a joint action [i.e., they performed the joint action], and that joint action is morally significant, then — other things being equal — the agents are collectively morally responsible for that joint action” (Miller, 2001, p. 68; see also Miller, 2006, 2020; Smiley, 2022).

For collective moral responsibility to be genuinely collective, two conditions must be met. The collective must (a) have “its own identity, its own intentions and perform its own action [and it must be] (b) held responsible in a way that accounts for its collective character … as a composite entity not an individual entity” (Giubilini & Levy, 2018, p. 195). Collective group action further requires the contribution of more than one individual for its performance; individuals do their part in bringing about a common end — or at least in bringing about different ends that ‘mesh’ and are not inconsistent with each other; individuals intend to bring about this end or these consistent ends; they recognize that others are doing their part in bringing about such ends; they intend to make their contribution to this type of end because they recognize that others are doing the same; and they are all aware of all these conditions. (Giubilini & Levy, 2018, pp. 209–210)

Group Accountability and Intersubjectivities

What might constitute group responsibility and accountability? Stewart et al. (2023) defined group (team or joint) accountability as “members’ expectations of being held accountable for their common actions or decisions [which are] the product of ongoing group member interactions … While individuals contribute to these dynamics, team accountability is a global phenomenon, unique and irreducible to individual members” (p. 694). That is, no one person can be responsible or accountable for the group’s unique actions and decisions (Giubilini & Levy, 2018; Stewart et al., 2023), although this longstanding assertion has been challenged. Smiley (2022) believed that individual group members can be morally responsible for harm caused by the group’s decision and queried how blame should be distributed amongst group members.

Notwithstanding, group accountability is defined as an emergent understanding of how things are done within the collective. This understanding depends mainly on “multiple evolving subjectivities rather than formal accountability structures. [This group] is a ‘forum’ for moral tensions that often must be worked through by the members themselves” (Stewart et al., 2023, p. 703). Harken Miller’s (2001) collective moral responsibility concept, which becomes relevant when collective actions have moral significance.

To elaborate, when engaging in transdisciplinary work, evolving multiple individual subjectivities (e.g., perspectives, opinions, and feelings) (Stewart et al., 2023) morph into intersubjectivities or shared understandings and meanings that emerge from interpersonal interactions among individuals. Members of the TD group are influenced by each other ultimately leading to mutual awareness of collective agreement or disagreement on matters (Després et al., 2004).

Thus, it can be suggested that TD group accountability “involves taking responsibility for [the group’s] decisions, monitoring progress, explaining choices, and count[ing] on members to meet their commitments” (Stewart et al., 2023, p. 695). Joint accountability is related to initial team trust and members’ willingness to be vulnerable to others’ actions (i.e., trustworthiness). It is associated with (a) identifying or having a sense of oneness with the group, (b) a commitment to the group and (c) the group’s perceived self-efficacy (i.e., belief in its capabilities to jointly achieve its agreed-to goal). The budding accountability mindset within the group (i.e., members expect to give an account of decisions with reasons) should deepen joint trust and commitment thus increasing transdisciplinary responsibility (Stewart et al., 2023).

Collectives Accountable to Collectives

Giubilini and Levy (2018) identified five types of collectives: (a) organized groups not dependent on specific individuals, (b) groups with bonds of mutual solidarity where not all members must act to effect an outcome, (c) groups that program (brainwash) individuals to act with group intentions and collective agency, (d) a random collection of individuals whose aggregated acts produce outcomes and (e) groups whose members perform joint actions that have morally relevant outcomes (e.g., transdisciplinary groups). It seems that transdisciplinary collectives are responsible to other forms of collectives rather than to individuals. As evidence of this assertion (see Table 1), transdisciplinary collectives were deemed responsible for or held accountable to the whole, all forms of life, humanity, the future, and the wider context, those outside an in-house environment (ripple effect), the nature-nurture dilemma, and students and learners.

Transdisciplinary Value Set

Rather than individual responsibility, collective and group accountability seems to be an inherent trait of transdisciplinary work. This key takeaway prompted a discussion of a TD (collective-imbued) value set to replace individual values, which initially inform interactions among diverse actors (i.e., sole subjectivities morph into shared intersubjectivities and intertwined fates) (Després et al., 2004; McGregor, 2025). To elaborate, complex, wicked problems are rife with value disputes (Funtowicz & Ravetz, 1992). However, while working together in transdisciplinary collectives, individuals’ competing value sets are eventually superseded by an emergent, agreed-to value set comprising humanistic values that keep the dialogue moving forward and may contribute to transdisciplinary responsibility for the outcome of collective decisions and actions. Humanistic values include humility, respect, trust, empathy, compromise, tolerance, accountability, collective wisdom, commitment, and collegiality (McGregor, 2011, 2025).

Inferred Evidence of Transdisciplinary Responsibility

Although authors did not define transdisciplinary responsibility, an analysis of their contributions (see Table 1) helped me infer their thoughts on evidence of it in action. I approached Table 1 with the stem statement: “People are responsible when doing transdisciplinary work together if they….” The entire collection in Table 2 represents powerful inferred evidence of transdisciplinary groups acting responsibly, which seemed to shift over time. Between 2003–2016 (#7–12), authors were concerned with the nature of knowledge, knowing and learning, and barriers to collaboration. Authors from 2024–2025 (#1–6) focused on complexities, connections, and consequences.

Implications for Management

As society and business practices advance and evolve, our “language adapts by creating new terminology to describe these changes [via] the creation and spread of neologisms” (Mercado, 2024, pp. 1–2). More than linguistic novelties, neologisms can represent emergent trends within disciplines and societies and serve as tools for engaging in discipline-related discussions. Management is no exception. Neologisms also serve as “cultural value markers” (Mercado, 2024, p. 4), which can include changes in management culture to embrace transdisciplinarity.

The effectiveness of a neologism depends on the extent of its adoption. Management practitioners and researchers must decide if the neologism — transdisciplinary responsibility — and how it was conceptualized herein (see Figure 1) is effective for explaining this phenomenon. Is another label (neologism) more appropriate for capturing the onerous accountability for team and joint decisions on those beyond the decision-making context? I think the neologism has potential as evident in the recent uptick in its usage within the last two years. After a seven-year gap, it finally caught on although in an undefined state. The fact that this young journal (started in February 2023) is named the Transdisciplinary Journal of Management (TJM) also speaks volumes. Its mandate is “to support a diverse and inclusive society of well-managed, high-performing organizations that instill individual dignity, ethical management, and a sense of social responsibility” (TJM 2025, para. 1).

The journal’s mandate intimates that its founders judged the management discipline and associated leaders, researchers, and practitioners primed for transdisciplinary responsibility. Indeed, all it takes is the introduction of a neologism for its potential uptake, and this introduction is now happening in the management discipline. Mühlböck’s (2025) very recent edited collection about the role of business for individual and collective flourishing mentions transdisciplinary responsibility in reference to management: “the understanding of interrelatedness and interdependency leads to a transdisciplinary fundament of economics and management science and as such to a ‘transdisciplinary responsibility’” (Mühlböck & Schmidpeter, 2025b, p. 95).

Management is responsible to the C-Suite, employees, shareholders, and stakeholders. Transdisciplinary responsibility pertains to the latter, innovatively called stakesharers by Torkar and McGregor (2012). Ismail et al. (2024) proposed that “the transdisciplinary management paradigm includes the scientific management paradigm, the human relations management paradigm, the human resource paradigm and the principled leadership paradigm” (p. 380). So conceptualized, transdisciplinary management becomes a cornerstone for managing complexity and acts by fostering the integration of diverse knowledge and the generation of creative solutions that transcend conventional approaches. Transdisciplinary management depends on flexible leadership to navigate uncertainty while striving for innovation (Segovia, 2025), and it would flourish if it embraced the transdisciplinary responsibility innovation.

Conclusion

Collective responsibility is an insufficiently conceptualized but very real phenomenon, especially in transdisciplinary work; yet little has been written about the neologism transdisciplinary responsibility. Moreover, the primacy of individual responsibility over collective responsibility in our society compromises understanding responsibility in joint initiatives (Bakeeva & Biricheva, 2021; Smiley, 2022) including management. The analysis herein supported the premise that the collective nature of transdisciplinarity makes transdisciplinary responsibility different from individual responsibility. This paper explored how collective transdisciplinary responsibility and interdependent, collective, and moral actions might be conceptualized (see Figure 1) and what constitutes evidence of manifested transdisciplinary responsibility (see Table 2).

Per the tenets of exploratory research, the findings, discussion points and ensuing conceptualization are intriguing enough to warrant further research (Yin, 1994). Thus, given the bourgeoning yet nascent scholarly interest in this idea, management scholars and practitioners are encouraged to ponder the conceptualization of collective and moral transdisciplinary responsibility presented herein. Complex, wicked problems are not going away. Insights into the responsibility dimension of transdisciplinary collective group work within management are needed to ensure transdisciplinary responsibility for humanity and the future.