I. Introduction

Both Japanese businessman Idemitsu Sazō (1885-1981) and social ecologist Peter F. Drucker (1909-2005) formed extensive Japanese Suibokuga (ink drawing) collections. With each taking the lead in his own way in the business field, they acquired a global perspective during their long careers, which extended from World War II through the Cold War. Drucker and Sazō understood the state of humanity and the logic of the interrelationship between the individual and the organization that honored different socio-cultural values in a changing society. This paper will explore how these two management virtuosos arrived at and developed their management principles and practices in conjunction with their deep appreciation of art in Japan. By analyzing their own words about artwork and management, this study sheds light on their belief in—and dedication to—the principles of social tolerance and the virtue of human resilience.

Although the Druckers established a world-renowned collection of Japanese ink paintings, the relationship between their art collection and Drucker’s management principles has rarely been explored in depth. Similarly, Sazō’s art collection has been mainly discussed in the context of art history, even though he admitted that the life lessons he learned from his art collection informed his approach to business.

Scholars have discussed the roles and meaning of a collection and its curation in many ways. They agree that collecting is driven by human curiosity and the attempt to understand the world. On the social and political level, art collections can serve as symbols of power and legitimacy. For Drucker and Sazō, however, the collection of works of art was initially a private affair. Each man, in his own way, fell in love with Japanese art. It was inevitable that their collections informed their view of what it means to be human and of how organizations function in a society in which artworks have been created. This paper, therefore, focuses on the nature of an art collection as an individual’s aesthetic and intellectual pursuit insofar as Drucker and Sazō share that love, interest, and social concern.

Studies of corporate art collections developed mainly during the West’s postwar economic boom. These studies mainly focus on the purposes and effects of art collections, that is, how they promote corporate identity, ethical behavior, and good citizenship, as well as support emerging artists. It is, however, hard to find research on how founders like Drucker and Sazō conceived artwork and how their collections helped shape their visions and the culture of the organizations they led. Such research requires a transdisciplinary approach to art, culture, history, and management. This paper is inspired by early studies on Japanese management, such as Motofusa Murayama’s Introduction to Management in Asia – Intersection Between Culture and Management in the East (1973) and Tadashi Mito’s Theory of “Ie” [family, house, clan] (1991), both written in Japanese. These prevous works situate management as a socio-cultural product in its specific historical context. Recent English-language studies include Organizational Culture and Leadership, 5th edition (2017), by Edgar H. Schein (with Peter Schein), which indicates the importance of the founder’s role in generating an organization’s culture. This article points out that culture is integral to organizational strategy, and, above all, that change in action is possible through defining one’s own culture in the face of an ever-changing world.

This paper will use a methodology relying on historical research to present a comparative analysis of Japan’s management culture as observed by Drucker and Sazō. It aims to cast a light on their art collections and textual information to define organizational culture and management principles in Japan. While following Drucker’s principle of management as one of the liberal arts, this paper will contribute to the current debate of changing management culture in Japan and in the world by examining the role of art collections in coming to know one’s own culture, the better to address the inevitable changes toward the end of organizational survival.

Drucker was aware of the emergence of the knowledge-worker sector and how they could work effectively in 20th-century society. Sazō treated workers as family members. He didn’t fire anyone, even though his company lost almost everything after World War II, and the company continued to honor this family principle. For many Japanese, Sazō is a national hero, a model of the protagonist of Naoki Hyakuta’s historical novel, A Man Called Pirate (2012). Foreseeing the limits of Japan’s energy resources, Sazō launched a small oil company in Kyushu, which worked for customers and tirelessly fought the major oil companies that had dominated the international oil market through colonial privileges.

As an immigrant to the U.S., Drucker, the scholar, was interested in the legal function of the state and its institutions. By contrast, having started his business with the mission of serving people, Sazō didn’t expect much from governmental bureaucracy. Rather, he found the roots of the nation’s foundation in the idea of ancestors. That is, Sazō conceived his company as a long-lasting independent unit like “Ie,” Japanese for “family,” “house,” or “clan.” In Japanese culture, the president or father of an organization ought to aim to secure the development and well-being of all its members for the duration of their lives.

How did their art collections inform their way of life and management practices? When did their thoughts on how a society functions come about? The last decade of Sazō’s life, spanning the late 1970s and early 1980s, marked a watershed moment for Japanese companies transforming themselves from traditional "Ie" organizations to Western joint-stock companies. For Drucker, the 1980s also marked a turning point in his doubts about the nature of private corporations. Both Sazō and Drucker believed that moral value is fundamental to personal growth and the management of organizations. Late in his career, Drucker’s thoughts increasingly overlapped with those of Sazō, whose management principles never changed. They shared the importance of social welfare and communal solidarity in maintaining a functioning society. Due to differences between Drucker’s and Sazō’s social values, however, their pursuit of a good society that tolerated diversity of values among its citizens took different operational forms. Until his death in 1981, Sazō pursued his vision of Japan’s family-oriented management style, whereas in the late 1980s in the United States, Drucker investigated the increasing role of non-profit organizations. Their flexible and forward-oriented management mindsets would have been impossible without their art collections that embodied them, and the inspiration these men derived from embracing their collections.

II. Sazō and Drucker as Collectors in their Social Background

The meaning and role of a collector change over time and place. Drucker’s practice of collecting belongs to the culture of the upper-middle-class, well-educated household in 19th-century Europe. Drucker mentioned that one of his relatives was a collector of the works of a minor but specific painter. In modern Japan, before World War II, many collectors emulated the great tea masters of the 16th century. The Zen monk Eisai (1141-1215) introduced the Rinzai sect of Zen Buddhism and the tea plant from China to Japan in the Kamakura period.[1] Having a cup of tea was practiced in Zen temples and then spread among the samurai (warrior) class as a way of spiritual discipline and consolation amid civil wars. Wealthy merchants also embraced the art of tea and established themselves as tea masters, appointed by a shogun (military leader).

Masuda Takashi (1848-1938), a prewar business magnate affiliated with the Mitsui Zaibatsu, hosted extravagant tea ceremonies filled with rare masterpieces from his massive collection and dazzled his guests.[2] The enthusiasm exhibited by Donnō (Masuda’s tea master name) for the tea ceremony was such that his business partners and colleagues naturally sought to practice the way of tea. To a degree, the tea ceremony served as a means for business leaders to confirm cultural values and artistic knowledge that helped them build mutual trust conducive to the pursuit of business. The Japanese penchant for collecting art and craftwork has been fostered in part by a culture to which the tea ceremony is critical. It is important to note, however, that Sazō never claimed to be a tea master, but admired the Zen philosopher Suzuki Daisetz (1870-1966), and they enjoyed a lifelong friendship that arose through the mediation of the late Zen monk Sengai Gibon (1750-1837), whose ink drawings and calligraphies Daisetz admired and Sazō collected.

Drucker and Sazō’s collections exhibit their differences in education, circumstance, and background. So far, Drucker’s name cannot be found in Sazō’s writings, but both collected ink paintings by Zen monks, including Sengai, and by literati painters from the Edo period. Drucker knew of the Idemitsu Museum of Arts’ extensive holdings of Sengai’s work.

Idemitsu Museum owns about one thousand works by Sengai, which form the majority of the museum’s painting collection.[3] Sazō recalls visiting an antique shop with his father. Sazō encountered Sengai’s painting and “fell in love” with its creator. That was his first purchase, and he continued to collect what he liked. Beside Sengai, Sazō’s collection includes ink paintings from the Muromachi period, works by literati painters and Ukiyoe in the Edo period, and major ceramic works of Old Karatsu ware, Chinese bronze vessels and ceramics, art objects from the Middle East, and other substantial works, such as those by painter Kosugi Hōan (1881-1964) and ceramist Itaya Hazan (1872-1963). In his preparation for the opening of the museum in 1966, Sazō followed advice from experts to extend the collection to include the systematic development of ceramics with a historical and geographical focus.

Like Sazō, Drucker confessed to having fallen “in love” with Japanese paintings. He recalled a mysterious encounter at the traveling exhibition in London in 1934. During World War II, Drucker worked in Washington, DC, where he spent his breaks at the Freer Gallery looking at Japanese paintings from the Muromachi period. His first lecture visit to Japan in 1959 was the occasion of his first purchase of Japanese paintings. His wife, Doris, later joined him, and it became the couple’s passion.

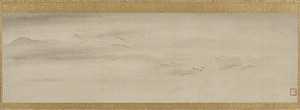

Drucker describes their collection as both a way of looking at a person and a way of life. They wished to live with those paintings and their creators in their everyday lives. Their collection may have been driven at first by their interest in the artists, but it also revealed their tastes and was fueled by their distinctive insights and individuality.[4] The couple’s collection of ink drawings could be characterized by a preference for, in their own term, "shibui" [austere, sober, plain] rather than for colorful or ornate artwork.[5] Drucker acquired two very different paintings, “Waves and Waterfowl” by Shikibu Terutada (Muromachi period, ink on paper with gold ground) and “Peonies and Butterflies” by Kiyohara Yukinobu (Edo period, color on silk) (Figs. 1, 2). Art historian Kawai Masatomo inquired, “What led Mr. Drucker to buy two completely different paintings such as these?” Kawai wondered whether Drucker saw in those works the expression of individualism in Japan or the flamboyant diversity characteristic of Western paintings.[6] It seems that Drucker intuitively followed his own polarity, sharing the characteristic he came to observe in Japanese culture.[7] Drucker perhaps added these paintings to his collection because they reinforced his assumptions of Japan’s ability to hold polar-opposite ideas and views at the same time without cognitive dissonance.

Although the Druckers’ tastes drove their purchases, their collection was built under the tutelage of a good teacher. The collection mostly focused on ink drawings from the Muromachi period and literati paintings from the Edo period, but also included early modern Zen paintings, and eccentric painters such as Itō Jakuchū (1716-1800) and Soga Shōhaku (1730-1781), as well as the Kōrin school and even older Buddhist paintings and Yamato-e.[8] Drucker’s teachers were highly established art historians as well as art dealers.[9] The detailed correspondence with these experts, including photographs, demonstrates the meticulous process by which the Druckers curated their collection, following the advice of specialists in both Japan and the U.S. Through this process, Drucker cultivated his perceptions regarding Japanese paintings.

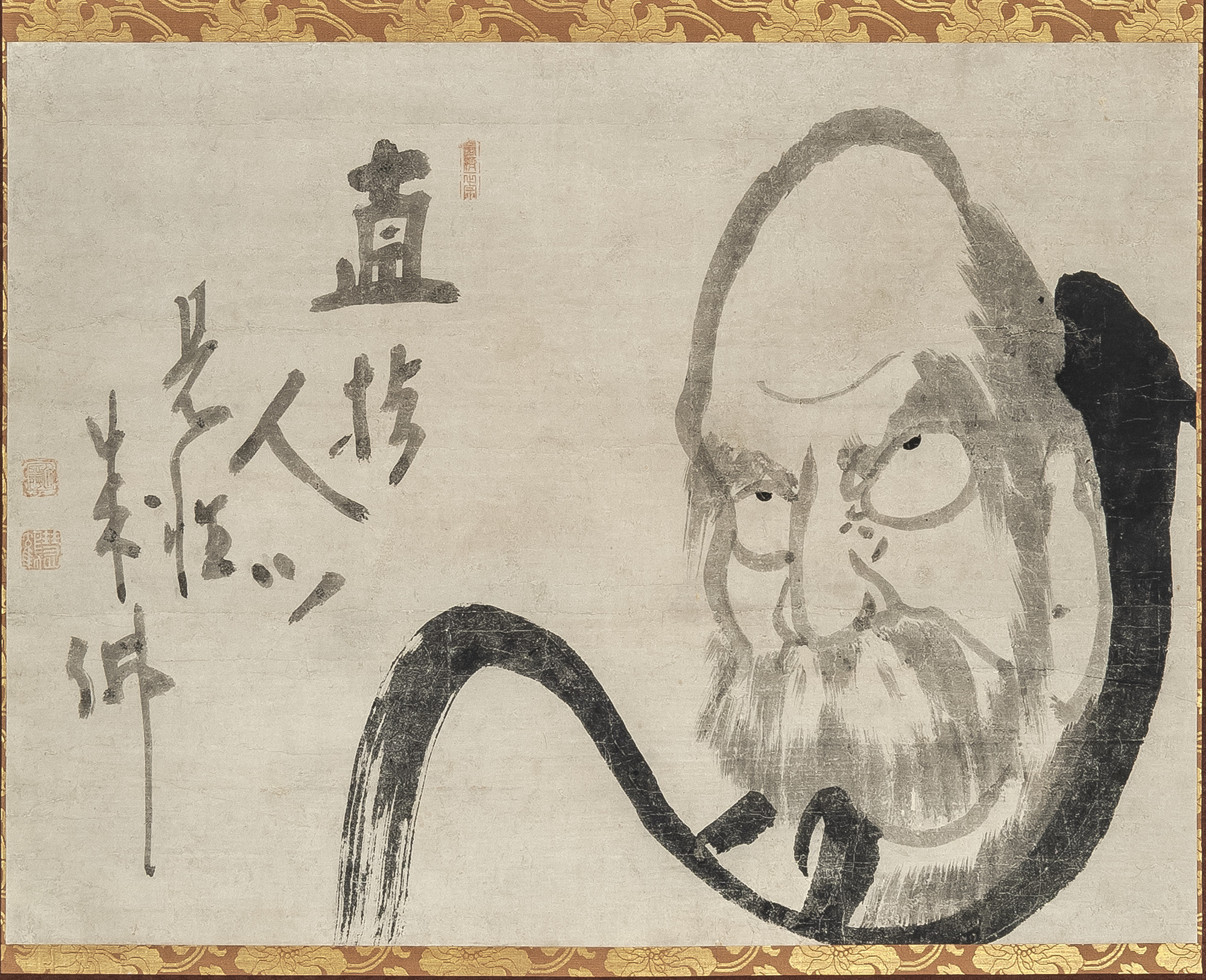

Compared to Drucker’s collecting style, Sazō’s seems more intuitive. He refers to his choices in emotional terms, such as “love at first sight,” rather than through a deliberate process involving academic consultations. He was also devoted to the artists themselves. According to his son, Idemitsu Shōsuke, Sazō adored Sengai so much that he erected a monument for the monk at Hōrinji Temple in Yokohama City, where Sengai had trained as a youth, and held a memorial service every year for this Zen monk and painter.[10] (Fig.3) Admiring their noble personalities and celebrating their work, Sazō wouldn’t hesitate to meet such distinguished living artists. Between 1900 and the end of World War II, many literary figures and artists settled in the Tabata area, near the Tokyo University of the Arts. Sazō visited ceramic artist Itaya Hazan and painter Kosugi Hōan. Through such friendships, Sazō’s collection grew naturally. Sazō himself couldn’t explain how it happened, but recalled that once he identified what he liked, such favored artworks mysteriously came into his possession without effort.[11]

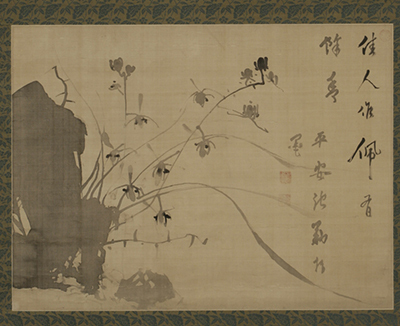

Drucker and Sazō didn’t keep their collections in storage, but preferred to live with them. Their collections offered them intimate perceptual experiences. It seems that the Druckers collected only hanging scrolls because that would fit easily on the walls of their Western-style house in Claremont, California. Their daughter, Cecily Drucker, recalled that there were always at least three hanging scrolls in the family home, and that her father frequently talked enthusiastic about these works, their artists, and their history.[12] Likewise, Sazō often asked for tea with his favorite Karatsu ware, “a tea bowl with a cross in a circle,” he called it, and also used the sake (Japanese rice wine) bottles from the old Kutani in the early Edo period.[13] (Fig. 4) For the public, every year Sazō had his organization print a calendar of Sengai’s paintings and calligraphies with Daisetz’s explanations.

Through using and looking at artwork daily, they confronted the spirits of their creators. Such interactions led to a deepening of their understanding of humanity and served as a spiritual guideline for their way of management. “I think Sengai’s teachings naturally infused themselves into me and into the management of my business,” said Sazō. “Isn’t it a unique feature of Sengai’s illumination that he could educate people by making people laugh? It’s rare to find such a monk,” Sazō also told his employees.[14] Drucker concurred: “The first late Bunjin [literati] painting, it seemed to us, demands of its viewers that they transmute themselves into the persona of the painter,” so that they could learn about themselves from literati paintings, which express “wholeness as a person,” this being a major driver of Drucker’s fascination with Japanese art.[15] For both men, art played the role of illuminating the essence of human nature, inseparable from their understanding of humanity and the principles of management.

III. Art and Management: Insight into Human Beings and Continuous Learning

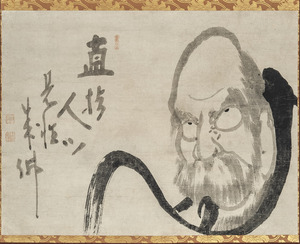

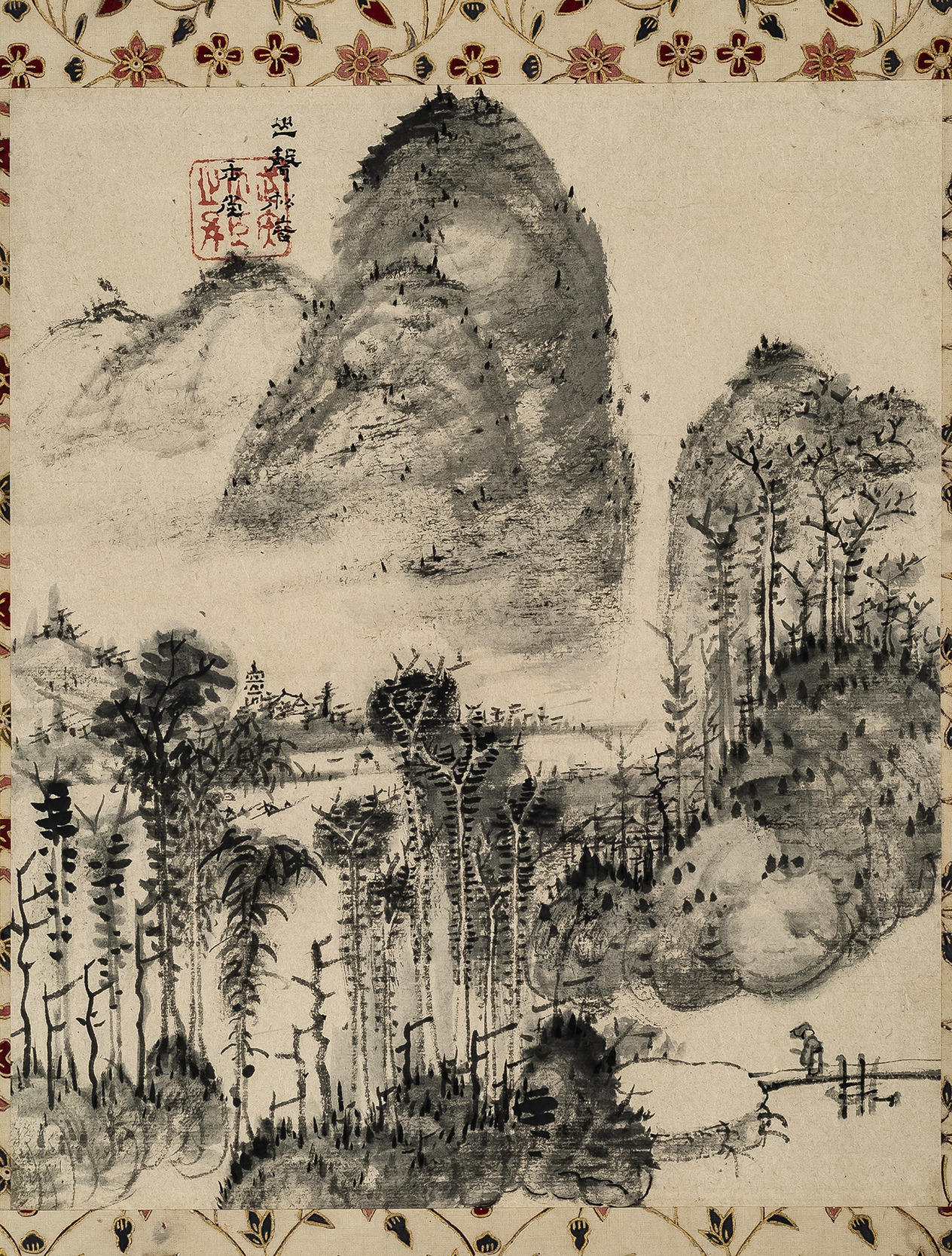

Behind their pursuit of the “moral cause” embedded in the welfare and well-being of organizations, Sazō and Drucker were learning from artwork. They observed moral and spiritual values in their art collections. Idemitsu collected mainly ink drawings and Old Karatsu ware, but when asked about the value of beauty, Sazō replied that the true value of beauty doesn’t reside in the art object itself, but rather in the state of minds of people and in their behavior: “True beauty is found in the sincerity of the human heart; works of art are just the means.”[16] Sazō wasn’t looking for the external beauty of ink drawings and calligraphy. Sengai was a Zen priest, not a professional painter. Responding to numerous requests from his followers, Sengai made many ink drawings with texts infused with Zen teachings after he retired in his sixties from the abbotship at Shōfukuji Temple in Hakata.

Zen teaching is focused on reality, as Suzuki Daisetz pointed out: “Zen always wishes to keep itself as close as possible to Reality, so that it will never wander out into the world of concepts or symbols.”[17] Likewise, Sazō saw that beauty lies in everyday reality, in the close ties of family, and in the establishment of world peace and welfare. It suggests that he conceived beauty and morality on the same ground: “I think beauty is something that people actually do.”[18] This suggests that Sazō embraced Zen teaching through his friendship with Daisetz. Sazō hoped that this moral could be shared by not only the Japanese but also the world’s many other peoples. He hoped that Japanese “morals [dōtoku]” would “establish world peace and human welfare” because they flowed naturally from the heart.[19] Sazō’s “sincerity,” fueled by the Zen way of action, may resonate with Drucker’s management practice of “integrity.”

Although Drucker placed moral determination primarily on the basis of the legitimacy of management and executive governance, he did not explain what he meant by morality. In fact, we have to consider that morality may not be absolute but may depend on complex circumstances. What is morally right can vary from one perspective to another. According to Karen E. Linkletter, the origins of Drucker’s ideas, which regard management as a culture, lay in Greek and Roman philosophy, which asked what made for the development of good citizens. The criterion for moral judgment is Aristotle’s “prudence as a virtue” and the development of an innate understanding of right action.[20] Regarding morality and moral judgment, Drucker leaves it up to everyone to hear his or her inner voice. Drucker doesn’t use lavish words, but maintains a practical tone. “Do I want to see a pimp when I look at myself in the mirror while shaving?” is a question Drucker repeatedly asks when the questions of morality and the integrity of an individual’s conduct come up.[21] (Fig. 5) Drucker was careful to acknowledge that the cultural norms of proper behavior varied, but demanded that leaders practice integrity in their actions regardless of the circumstances.

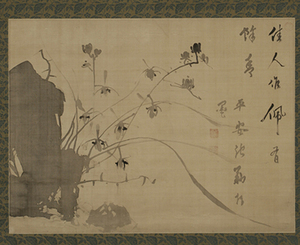

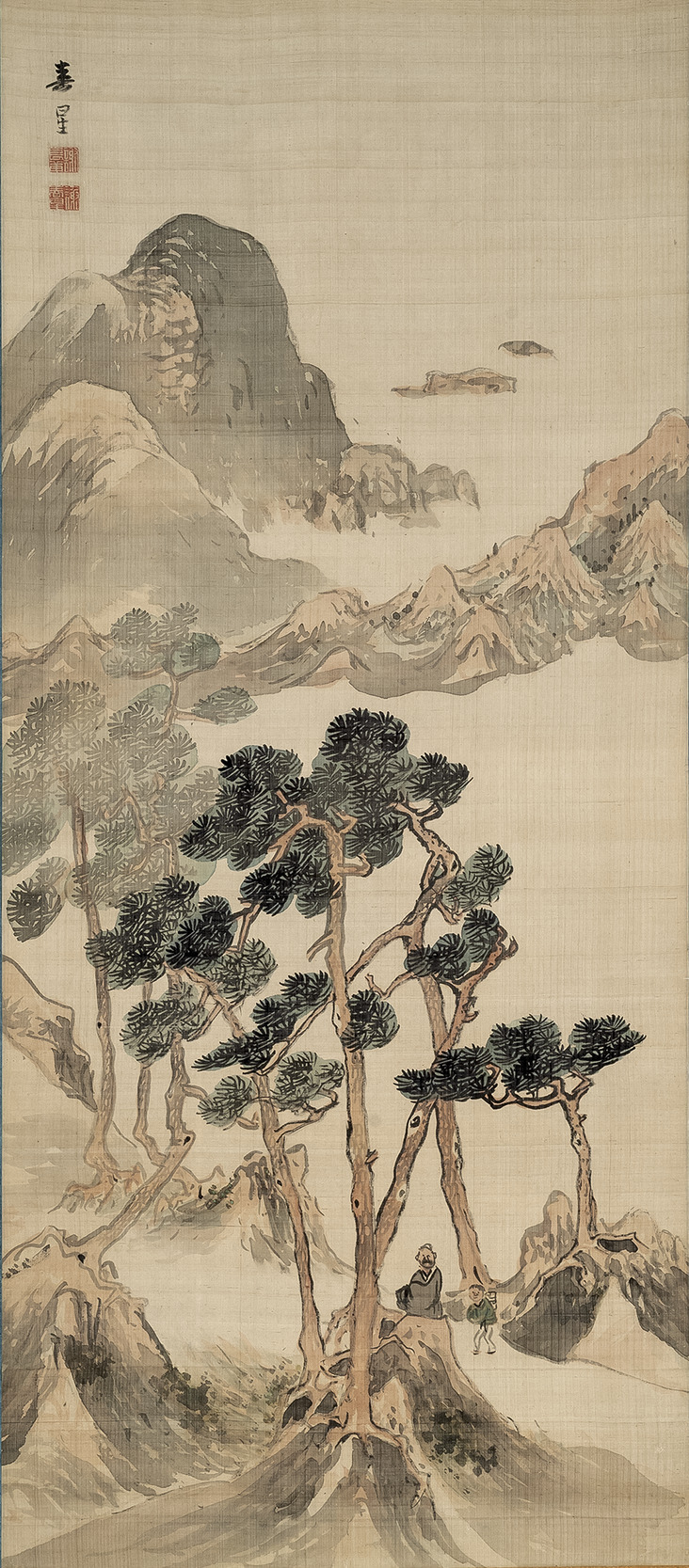

Early Bunjin [literati] painting emerged in China during the later Han Dynasty (around the second century C.E.) and had a major impact on Japan much later in the middle of the Edo period in the 18th century.[22] As the word suggests, literati paintings were created by the highly educated elite ruling class for their pure enjoyment. These scholar bureaucrats were not only well-versed in the classics of Confucianism but also studied Taoism and Buddhism. Unlike professional painters, they were brilliant amateurs who engaged in creative activities as a hobby. The literati favored the spiritual quality of austere ink paintings because they held that landscapes projected noble integrity. Literati painting peaked in the mid-10th to early 12th century, during the Northern Song Dynasty. There is no stylistic uniformity in literati painting, but landscapes with layers of gentle, delicate lines emerged in Jiangnan, in the southern region of China, and their works came to be known as Southern Song painting. As scholar Yoshizawa Tadashi points out, 400 years later, in the 18th century, those Southern Song paintings were well received in Japan along with other Chinese paintings. These Japanese followers’ works were called “literati painting” or Nanga. At this time, Japanese painters sought new artistic inspirations from abroad because established traditional schools lacked innovative vitality and essence in their paintings.

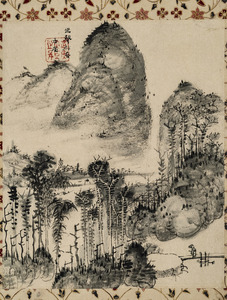

According to Yoshizawa, there was no social status in Japan equivalent to the landowning Chinese literati bureaucrats. There were samurai who were well-versed in Confucianism, but their livelihood was modest and unstable. If they showed outstanding promise in painting, they were criticized in their feudal domain for indulging in the arts. This tendency seems more prominent in the east (Edo, old Tokyo) than in western Japan because Edo was the bureaucracy’s political center. In fact, the artistic establishment of so-called literati painting in Japan was achieved by professional painters, namely Ike Taiga (1723-1776) and Yosa Buson (1716-1784) (Fig. 6, Fig. 7). Notable painters from the samurai class, such as Uragami Gyokudō (1745-1820) and Tanomura Chikuden (1777-1835), generally practiced after they resigned from their feudal clan. (Fig. 8, Fig. 9) Due to their strict isolation, the Japanese had to teach themselves literati paintings through imported paintings, illustrated textbooks, and Zen monks from China. Importantly, there was a shared principle that a painter has to read many books to clear out worldliness in literati painting.[23] Reading is the foundation of superior literati painting; the deliberate learning attitude of painters is inevitably shown in their output.

It seems there is no coincidence that both Drucker and Sazō favored and collected ink paintings by well-educated painters who valued free expression and the pursuit of the spiritual realm. Inspired by Japanese ink drawings, Drucker and Sazō emphasized the importance of continuous education and learning. Furthermore, both conceived of human beings as imperfect. Sazō observed a human being this way:

It’s impossible to make a human being a god or a Buddha. There are two sides to human beings: those that are respectable, such as gods and Buddha, and those that are not. I call this divinity and beastliness. Therefore, it is wrong to see human beings as perfect as God or Buddha, and on the other hand, it is also wrong to identify them with beasts. I believe that the interesting aspect and difficulty of human society lies in the fact that a human being has desires and makes mistakes. As human beings, we must strive to control our beastly nature and elevate our divinity as much as possible.[24]

It was crucial to forgive errors because humans are not perfect, and Sazō claimed that Idemitsu Kosan Co., Ltd. did not penalize employees for their failure.[25] However, Sazō admitted that not all humans are “equal” because there are both good and bad ones, so management should be “fair” in creating a work environment where people can engage with what they want to do, and recognize their contributions. In his view, employees should conceive of work as a means of self-realization, and one’s salary is not an end in itself but rather a guarantee of having enough to live in dignity. Tolerance toward what is lacking in one’s employees doesn’t mean overlooking their irresponsibility, but rather giving them due attention and discipline. Failure is seen as a tuition for bitterly earned business lessons.

Similarly, Drucker had a Judeo-Christian belief in human imperfection. Having witnessed the rise of totalitarianism in the 1930s and the collapse of the economy, he had an insight into human weakness and despair. In his memoir, Drucker wrote about his grandmother’s compassion for her relatives in Austria and her teaching of “nosiness” and “tolerance” in the 1930s. On a bus, she once admonished a young boy with a swastika, appealing not to politics but to the virtue of tolerance. Her criticism, which reflected the moral education of the Drucker family, serves as a root of a well-functioning society in which each individual has a role in contributing to a diverse and tolerant society.[26] Meanwhile, in the community of the Zen monastery, Daisetz wrote about his favorite story of Sengai and his delinquent disciple, a story that suggests “tolerance” toward the Zen monk.[27] Sengai noticed one of his disciples leaving the monastery at night and returning in the early morning. One morning, when this disciple climbed down the monastery’s fence, he noticed he was stepping on something soft, which turned out to be the crouched back of Sengai, who tried to support his disciple safely. The disciple was ashamed, but Sengai uttered no condemnation, quietly sending his disciple to his quarters.

With tolerance in mind, Drucker and Sazō respected the individuality of human beings. Drucker’s attitude about the importance of individuality and learning was shaped by his own unique education in his childhood. Drucker went through the progressive New Education at a private primary school in Austria. Unlike other primary schools, for instance, all students were encouraged to use hand tools and make things, thereby showing respect for craftwork.[28] This hands-on, student-centered way of learning starts with the pupil analyzing the strengths and weaknesses of his subjects with a teacher, setting specific goals, planning schedules, checking his progress, and reshaping the goals and plans so as to obtain projected outcomes. This learning strategy corresponds to the present-day PDCA cycle. Drucker applied the lesson he learned in childhood in the development of the principle of efficient management, which emphasized individual strengths.

Spontaneous learning became critical as Drucker observed that the number of higher education graduates increased with the country’s economic growth in the 20th century. This structural change in the human labor force formed our knowledge society, characterized by the rising numbers of knowledge workers equipped with specialized knowledge. Knowledge workers need incentives and goal-setting because they cannot be managed unless they see that their projects have meaning.[29] Hence, Drucker and Sazō thought that motivation is essential, and fair evaluations and fulfillments achieve human development.

IV. Self and Others: Transnational Management and Culture

Regarding their reception of Japanese ink drawings, both men recognized the presence of space within the picture planes. Drucker tried to explain this Japanese aesthetic quality using Western concepts of topology and Gestalt psychology. For Sazō, the empty space was associated with the free spirit of Zen, which he learned from Daisetzu. The creative impetus driven through the human perception of empty space was noted from a neuroscientific viewpoint in the previous essay.[30] Here, it attempts to extend the argument toward the transnational management practices.

Drucker wrote:

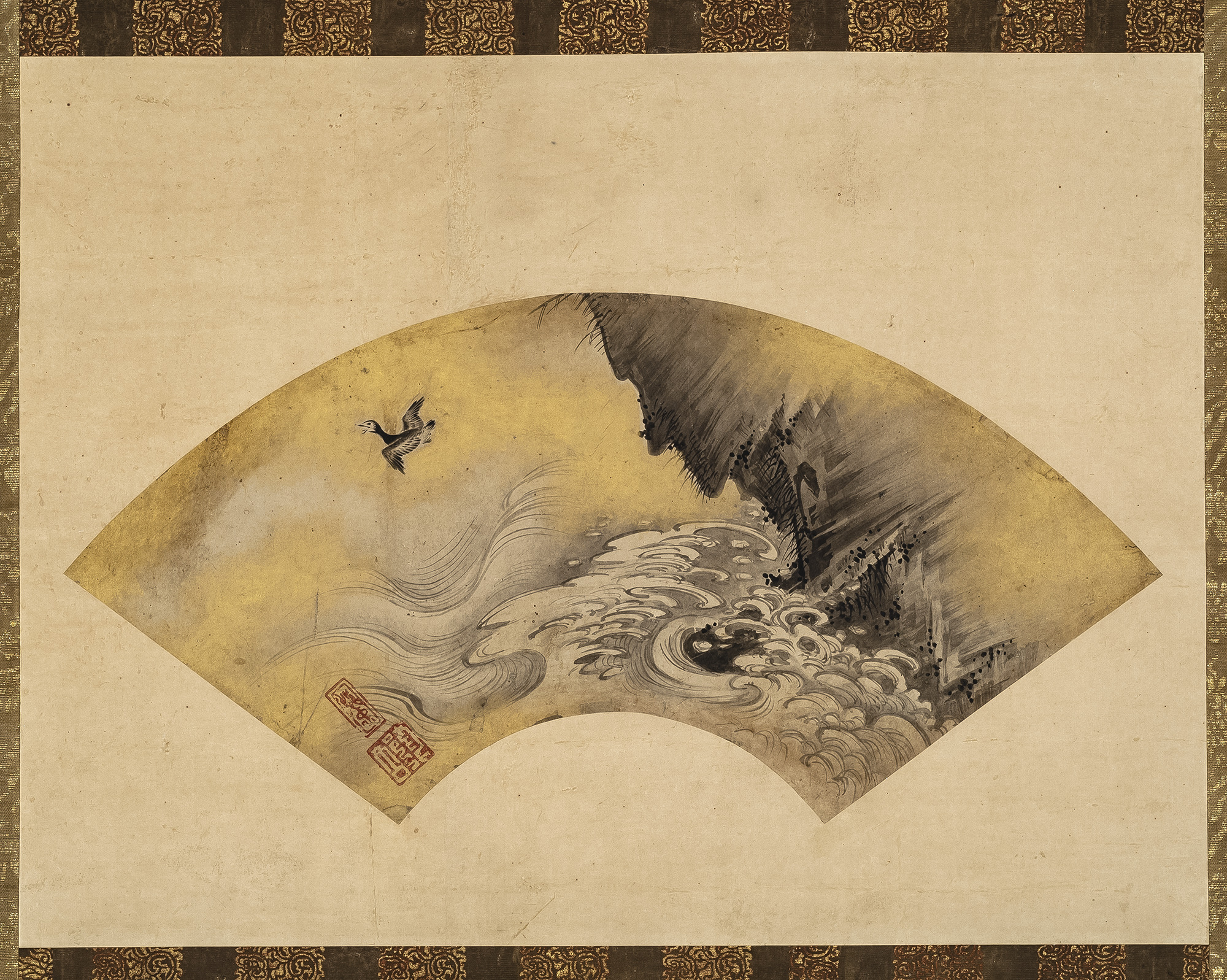

The Japanese paintings are dominated by empty space. It is not only that so much of the canvas is empty. The empty space organizes the painting. This is the opposite of what most Chinese painters would do, but it is basic to Japanese aesthetics. The same aesthetics are found, for instance, in the Sansō Collection’s small fan painting by Ogata Kōrin, a painter who did not go to school with the Chinese, or Kazan’s very late paintings.[31] (Fig. 10, 11)

Similarly, on the occasion of the Sengai exhibition of 1955, Sazō had a conversation with the director of the Art Museum in Oakland:

Your [Western] paintings don’t have space for a viewer to enter the picture plane. If there is a tree on a blank paper in Japanese paintings, there would be stones, or a flow of river emerge in the minds of viewers. There is a space for the viewer to enter. However, the surfaces of paintings outside Japan are covered up, and there is no room for us to enter.[32]

Sazō imputed a moral dimension to the use of empty space by arguing that it represented the artist denying his ego. (Fig. 12) For Sazō, art was not a means to project the artist’s desire for fame and recognition, but a higher pursuit that transcends a self-centered human ego. He was not interested in artworks that displayed technical sophistication and meticulous ornamentations solely to impress the viewers. Rather, art is about selfless acts, acts undertaken for the sake of others. Sazō preferred to find this selfless state of mind in both Japanese paintings and Old Karatsu ware. This became integral to his theory of management in the changing world in the post-World War II era.

Pluralism embraces diversity, but Drucker avoided openly discussing his identity or religious beliefs. In contrast, Sazō identified himself as an “ethnic manager,” distinct from the management of the dominant international major oil companies, also known as the Seven Sisters in the 1970s.[33] Drucker dealt with the word “culture” carefully due to the vagueness of its definition, but wrote an article in the Wall Street Journal, “Don’t Change Corporate Culture – Use It!” (1991). It attracted widespread attention, although it is often misquoted as: “culture eats strategy for breakfast.”[34] Drucker did not use those words, but he meant that “Culture, no matter how defined, is singularly persistent.” In the above-mentioned “Japanese in Japanese paintings” (1979), serious economic issues such as agriculture and trade inequality, which have lost competitiveness due to protectionist policies, require critical attention, but Drucker concludes that it is not economic policy that needs to be altered, but rather Japan’s social structure, social policies, and values themselves.[35] In other words, without changing the mindset of people, real change in society will never occur.

In his 1969 keynote speech in Tokyo, Drucker paid attention to the role of culture in management. He stressed that management should follow universal principles, yet organizational change could be achieved through embedding existing cultures into the principles. Management is both a science and a humanistic discipline that connects a globally expanding “civilization” with “culture,” which is expressed through diverse traditional values and beliefs.[36] In 1975, Sazō noted a similar principle of management based on rational decision-making and flexibility in choosing imported ideas, technologies, and practices to generate his own business model:

[We are] taking the good part of capitalism and discarding the bad part. Capitalism offers a merit in working freely and improving efficiency. And the bad side of capitalism is that the wealthy can take away the earnings from workers with the power of money. We don’t have capitalist, so nobody can take away the profit. We abandon the bad part of capitalism. We adopt the benefits of capitalism for working freely and increasing efficiency. Socialism focuses on what is good for working people. We incorporate that aspect but do not adopt the inefficiency of the state-owned business model. Also, we adopt communism for the point that it is for the sake of the working people, but we abandon its evil equality, and we do things fairly. These three things have been incorporated into my company.[37]

The above discussion suggests the issue of how the domestic management model could be evolved into an international operation.

The integration process of domestic and overseas operations could be characterized by four models from the perspective of Japan-U.S. comparative management: ① convergence, ② natural harmony (or) disharmony, ③ dominant control, and ④ mediation equilibrium.[38] Each is summarized this way: ① both sides reorganize the traditional value system to prioritize efficiency; ② natural harmony happens through transfer and develops mutual value systems together, whereas the phenomenon of natural incongruity is the result of excluding alien elements; ③ the dominance of the superior promotes the advantageous system of industrialization and democratization in an economy’s development stage, facilitates change, and reorganizes the core nature of the culture; and ④ mediation equilibrium is the role of mediator: a “change agent” that creates a bridge between different cultural dynamics through foreign experiences and international perspectives.

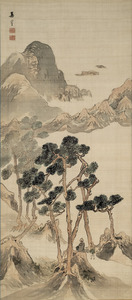

For Drucker, a transdisciplinary perspective of management was driven by what he observed in the arts, e.g., how Japanese ink painting differs from Chinese painting and how Japanese artists receive and reject foreign influences in their artworks. Drucker learned through works by Sesshū (1420-1506), a Zen monk and ink painter of the Muromachi period who went to China and studied Chinese ink paintings. Instead of falling into hybrid painting, Sesshū achieved his expressions through looking at his native land and nature, infusing his own sensitivities and projecting the teachings of Zen, as Drucker recognized. Before Sesshū, Zen monks typically enhanced landscape paintings with poetry written on the same scroll; texts and pictures complemented each other. This format was popularized by Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (1358-1408) during his reign.[39] Art historians agree that Sesshū made landscapes independent from poetry through the expressive potentials of ink brushstrokes and infinite tonality. Having focused on capturing nature’s reality, Sesshū established the autonomy of ink painting as refined artistic expression in Japan. Referencing this lesson from Sesshū, Drucker analyzed the foreign influences that resulted in something internally persistent yet changed in Japanese management.[40] (Fig.13)

what makes Japan more Japanese

what fits topology rather than geometry or algebra

what fits Japanese human relations

what fits the inner experience of the uniqueness of Japan …Japanese spirituality[41]

Sazō and Drucker’s writings suggest the possibility of integration with heterogeneous factors by ① convergence and ② natural harmony (or) disharmony; they both acknowledged the possibility of integrating different values and practices in organizations, while recognizing the persistent cultural values in Japanese society. A painter and Zen monk, Sesshū, demonstrated ④ mediation equilibrium; Sesshū introduced Chinese ink paintings to Japan and sublimated them to his own artistic expressions and became an influential change agent in Japanese ink paintings. ③ Dominant control is backed by globalization, forming a control-vs-subordination relationship, but even such a situation provides a business opportunity for those with a determined strategy. For example, the Idemitsu Shop in the 1910s, at the early stage of its founding, developed a special ship equipped with a fuel-oil measuring instrument for fishing vessels to handle business at sea because the land-based market was legally restricted to a competitor.[42] Furthermore, in the Manchurian market controlled by European and American oil companies, Sazō boldly entered sales channels by developing high-quality axle oil, fulfilling local needs in the railroad industry. It also suggests that for Drucker and Sazō, management is an art and transdisciplinary pursuit, requiring flexibility, creativity, and resilience at all operational levels. This requires redefining reality in terms of the relationship between traditional values and culture and international ideas and technologies.

V. Self-Fulfillment: Working at NPO and Organization as Enduring “Ie”

Having faced the madness of the 1930s, Drucker envisioned “a functioning society” during the 1940s.[43] He knew there was no shortcut to realizing a well-functioning society, but also believed that broad exposure to many educational disciplines within the liberal arts tradition fostered critical thinking and a sense of personal responsibility. As Linkletter discussed extensively, Drucker found the essence of liberal arts education in Western classical philosophy, fostering an idea of citizenship with social values. Each citizen is free and responsible—that is, able to think thoroughly and act independently while respecting pluralism to avoid dictatorship.[44]

Drucker and Sazō absorbed the educational potential in artworks they collected. Drucker knew that the psychological dimension of the individual affects the functioning of society, whereas Sazō paid attention to the spiritual realm of human beings in organizations and society. Sazō managed his company as a family and looked after his employees’ welfare. Since “welfare” is difficult to define, Sazō thought about the meaning of unhappiness. He concluded that even if he could be totally free, “being alone on an isolated island is the greatest unhappiness,” and defined unhappiness as the opposite of happiness. For Sazō, “happiness” is when two or more people can get along without confrontation.[45] In Sazō’s view, happiness is community. In contrast, Drucker, who experienced Nazi totalitarianism, which deprived individuals of virtually every degree of freedom, prioritized the individual’s freedom as a foundation of happiness.

Sazō believed that individual capability is essential to the organization, but he was critical of Western individualism. He didn’t believe that individualism would fit into the cultural soil of Japanese organizations without resulting in selfishness and demands for rights and personal gain.[46] He thought that the true power of the organization would be demonstrated by the “selfless unity” of the individual, as an “individual for the whole,” rather than an overly strong individual.[47] This doesn’t mean that the Japanese are mentally driven toward collectivism or retain remnants of feudalism. Organizations will fail without meritocracy. It should not be oversimplified, but “individualism” in Western society has been associated with social responsibilities and good citizenship. Sazō’s claim suggests that these aspects of individualism have been diminished by an emphasis on “freedom” when the Japanese imported this idea.

In Western societies, knowledge workers, whose philosophical base is the primacy of the individual, seek an organization in which their abilities can be utilized. By contrast, Sazō prioritized respecting everyone and being a family-oriented company with sustaining employment. Sazō was influenced by his teacher Mizushima Tetsuya (1864–1928), the principal of Kōbe Kōshō (now Kōbe University), who taught that a business should be run with compassion, similar to a family.[48] While colleagues and family members are different, the head of a company carries a moral responsibility just as the head of a household does. Another major influence at Kōbe Kōshō was Uchiike Renkichi (1876–1949), who emphasized that management is not focused on making money but on fulfilling a social duty by serving customers. In this view, profit is not the goal but rather a social “reward” for running a business properly.[49] During World War I, people made fortunes from the boom in munitions and other industries, and the young Sazō witnessed the moral corruption that infected these businesses and Japan’s social atmosphere.

Management scholar Mito Tadashi discussed the historical and cultural context of modern Japanese organizations in Ie no Ronri I, II [The Logic of Family] (1991). The lifetime employment and seniority system became customary as it helped to overcome the shortage of workers and secure employees for a long time during the industrial transition, and it continued even after World War II. Mito pointed out that this transformation of industrial structure in modern Japan followed the logic of Ie (family, house, clan). The logic of Ie prioritized the survival and prosperity of the family under the shogunate system. The Japanese corporate organization inherited this family-oriented social bond because there had not been enough legal reforms.[50] To protect their economic profits, factory owners firmly resisted government efforts to reform labor practices under the 1911 factory laws, which ultimately were not enforced until 1916. Since the law didn’t carry much weight, it relied on the mercy and benevolence of the factory owners to win the workers’ loyalty.[51] This prevented major chaos or upheaval to some degree because it preserved the conventional pattern of social relationships and order. After World War II, this benevolence extended to corporate welfare programs.[52]

According to the logic of Ie, the company is a house, the president is the head of the household, and its survival is more important than profit. Typically, the stock is owned by the founder’s family, and even if it is legal, it is blamed as a “takeover” when outsiders buy up the shares.[53] Unlike the notion of family in China and Korea, Japanese Ie is not necessarily bound by a bloodline. Drucker misinterpreted this logic of Japanese family organization as a synonym of a hereditary system, the pre-modern Western “family business.” Discussing the cases of the DuPont and Rothschild families, he insisted that accepting outside professionals is necessary for the survival and growth of organizations.[54] That is true with Japanese organizations too, but it seems Drucker was not aware of the Japanese hidden principle of competence-based management in which capable employees, who were not blood relatives, were incorporated into the executive branch as adopted children or “right-hand” men for the founder’s family for the sake of the company’s survival as Ie.

For the sake of the organizational endurance, the logic of Ie is not unique to Japan, as Drucker witnessed. Mito further points out that the meritocracy of Ie is layered with hierarchy, e.g., blood relations, family status, the dialectic between the parent company and subsidiary company (head family and branch family), and higher education, all inherited from the feudal clan system.[55] It gives internal order to the organization, but its weakness is the stiff bureaucracy it engenders. Sazō’s “familyism” should be understood in this historical context and logic of “Ie”, but having been educated at the business school, he also had a liberal idea of management. Sazō’s teacher/mentor, Mizushima Tetsuya, who worked in New York as a banker, required his students to read The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, filled with an independent spirit and lessons of self-governing in all circumstances.[56] In addition, Sazō’s father strictly taught his son to be independent and work throughout his life.

In the 1990s and 2000s, one and two decades after Sazō’s death, Drucker faced a strange reality, even a contradiction. He had a renewed interest in the condition of knowledge workers and their well-being. He passionately discussed non-profit organizations in 1990: “One of the great strengths of a non-profit organization is that people don’t work for a living, they work for a cause (not everybody, but a good many). That also creates a tremendous responsibility for the institution, to keep the flame alive, not to allow work to become just a ‘job’.”[57] He even asked the leader to ensure an enjoyable work environment; “The effective non-profit executive finally takes responsibility for making it easy for people to do their work, easy to have results, easy to enjoy their work. It’s not enough for them, or for you, that they serve a good cause. The executive’s job is to make sure that they get results.”[58] This emphasis on empathy, on fostering a caring attitude toward volunteers, resonates not only with Drucker’s stories about his grandmother but also with Idemitsu’s family-oriented workplace, marked by mentorship, brotherhood, and sisterhood.

Drucker pointed out that the non-profit organization is a true model for effective management in Management of Non-Profit Organizations (1990). In the same year, he committed himself to establishing the Drucker Foundation to offer training programs for leaders of NPOs, and Drucker took an active role in managing the organization. It seems ironic that Drucker’s writings of the 1990s indicate that for-profit organizations had to model how unpaid people work in non-profit organizations. For Sazō in the 1970s and Drucker in the 1990s, their “principle of working/well-being” corresponds despite the distance of their generations and countries.

Meanwhile, a decade after Sazō passed away, the economic bubble burst. In the 1990s, Idemitsu Kosan Co., Ltd. gradually fell into financial difficulty; it was too big to be privately owned. The global-standard evaluation introduced a ranking system that affected this Japanese company’s bank loans. To survive, it had to follow the open market, which required the joint-stock company to be owned and held by shareholders. Deregulation following the Petroleum Industry Law in 2002 caused widespread confusion, excessive production, and competition in the oil industry. When the U.S. government promoted deregulation in the 1980s, Drucker must have foreseen the kind of corporate mentality and behavior that would escalate and affect knowledge workers.

Tembo Akihiko, the former president of Idemitsu Kosan Co., Ltd., carried out the “Idemitsu Revitalization Project” and put the company on the First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange in 2006, while keeping intact the management philosophy of the “tenshu” (“shopkeeper,” as Sazō’s employees called him).[59] Sazō believed that the principles and practices of management were generated and transformed locally over time, so they would not be judged solely from an outside perspective. This cross-cultural understanding of management was based on the experiences that Sazō’s company had upon entering foreign markets in Asia and negotiating with foreign businesspersons before and during World War II. Nobody knows how Sazō would have reacted to his company being listed on the stock market, which happened after he passed away.[60] While he was alive, even though Sazō’s company was in the form of Co., Ltd. for convenience, it was run as a privately-owned shop, different from the formality of a Co., Ltd., which developed in Europe and separates ownership from management of the stock. Sazō saw that management responsibility was clear in the privately-owned shop but not in the corporation.

Drucker concluded that Japan was the only country that seemed to have succeeded in forming business as a community enterprise, but that lifetime employment in Japan still did not fit the reality of a knowledge society. Drucker was aware of the social evolutionary theory of sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies (1855-1936), who noted that the modern corporation is no longer a “community” but a “society.”[61] Drucker saw that the challenge for non-profit organizations in the 21st century would be to create communities in cities. In other words, in Drucker’s argument, corporations are not the place for knowledge workers to find their “community.” This is contrary to how Sazō saw his company. By the late 20th century, Drucker argued that the social sector, not the private sector, would provide community for knowledge workers.

Furthermore, Drucker anticipated the educational impact of non-profit organizations on individuals. He wrote, “The non-profits are human change-agents. And their results are therefore always a change in people – in their behavior, in their circumstances, in their vision, in their health, in their hopes, above all, in their competence and capacity.”[62] This can be achieved because, in managing non-profit organizations, social and moral causes rather than economic priorities drive the mission. The moral purpose of a non-profit is grounded from its outset, and its focus is on how it can function better to serve its community sustainably.

While Drucker emphasized the role of the individual and Sazō the team/family effort in his organization, both men were concerned with moral judgment, personal development, self-fulfillment, and the well-being/welfare of knowledge workers. They perceived realities and generated solutions based on their own social values. Sazō followed the logic of Ie (family/house/clan), viewing the organization from an internal perspective where employees are treated as family members, so the well-being of its members is the responsibility of its president/head of house. In part, this was a legitimate solution due to the insufficient legal infrastructure for non-profit organizations while Sazō was alive, and to its alignment with the social value of Japanese people in finding their “community” in a company after World War II. Following the logic of the corporation, Drucker saw that for-profit and non-profit organizations served independently in the U.S.; the role model of the knowledge worker is found in the NPO, so the two organizations are intertwined and anchored in the continuous human development that is integral to a functioning society.

VI. Silver Lining: the Public Benefit of Art Collections

Seeing a changing world, Drucker and Sazō thought about the future. Sazō remained optimistic and trusted his company’s younger generations. In his book, Drucker predicted that organizations would be managed by “strategy” in 2025, and that the task of leaders would be to manage collaborations across disciplinary fields.[63] It suggests that knowledge workers will deepen their specialized knowledge, and leaders are expected to take a role as conductors with a vision that generates whole projects. What is the legacy of their art collections in 2025? What visions did Drucker and Sazō leave us through their collections? What would be the destiny of their entire art collections after they passed away?

A private collection is about the collector’s vision. Philosopher and cultural critic Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) observed that the collector’s responsibility is to inherit the entire collection intact.[64] If the collection loses one of its pieces, it loses its artistic value and becomes just an item with a price tag. There is the belief that a collector saves the piece by choosing it; once it leaves the collection, it is at the mercy of the market. The unity of the entire collection is lost.

Collectors saved each piece of art from the market, thereby creating a public good out of the collection. Sazō was humble about his sole ownership of artwork: he saw his collection as intended for the Japanese people. He designated the private collection as a public treasure. Sazō created the Idemitsu Collection, which was organized in 1957 and opened its doors to the public in 1966. Following the advice of art historians and scholars in 1961, the entire collection has evolved with a scholarly perspective to encompass systematic narratives. Fields of study and specialists have included the History of Eastern Ceramics (Koyama Fujio), the History of Japanese Paintings (Tanaka Ichimatsu), Chinese Art (Sugimura Yūzou), Near Eastern Studies (Mikami Tsugio), and the History of Buddhism (Furuta Shōkin).[65] The museum is managed by the Public Interest Incorporated Foundation’s Idemitsu Museum of Arts, and its subsidy goes beyond research projects to include welfare programs. It is not common to find an art museum in Japan that subsidizes welfare facilities and the care of orphans from traffic accidents.

The Druckers were fortunate that their collection remained intact and was purchased anonymously by a Japanese corporation. The company entrusted the whole Drucker collection to the Chiba City Museum of Art. Posthumously, Drucker managed to acquire the collector’s ethical commitment, which honored all the artists Drucker had known. We can envision Drucker’s perspective of Japan through the entire collection. It provides clues as to how Drucker gained insights from each art piece while discovering Japanese society and its values. The focus of the Drucker collection was on ink drawings from the Muromachi period and literary painters. Literary painters in Japan were professional painters with independent, genuine creative minds who pursued their way of life. Zen paintings were also made by enlightened spirits. These spiritually driven paintings flourished within the feudal order and logics of Ie in Japan. It seems that their diverse creative impetuses were necessary resources for unleashing potential changes in society, even though their force has a subtle impact. Their significance was discovered and cherished by Drucker and Sazō under their shared vision of humanity: the uplifting of spirits and motivating beneficent human action.

VII. Conclusion

Both Drucker and Sazō faced human imperfection and emphasized the necessity of continuous learning. They sought a “functioning society,” each in his own way, but they both conceived that employees and knowledge workers need motivation, fair evaluations, and commitment to their community, whether in the form of a company, a non-profit organization, or a Ie. For Drucker, human well-being and a peaceful society were based on a pluralistic society that prevented totalitarianism, where human beings had freedom of choice and responsibility while fulfilling a purpose in life as they contributed to society. For Sazō, a functioning society was based on Ie, the organizational unity and longevity of the family, which was maintained by treating employees as members of a family.

Sazō, who continued to embrace the family-oriented organization, died in 1981 at the age of 95. While concerned about the extremely high remuneration of executives of joint-stock companies and their short-term strategy of profits, Drucker published Managing Non-Profit Organizations: Principles and Practices in 1990, when he was over the age of 80, and expected the increasing role of non-profits in society. Idemitsu Kosan Co., Ltd. did not change the fundamentals of its management philosophy, based on the family principle, to overcome its financial crisis and achieve sustainable growth, and in 2006, it listed the company on the First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange. Following Tönnies, Drucker concluded that two independent organizations of profit and non-profit business would be necessary for the “functioning society” in a knowledge society.

When management is considered to follow the steps of progress, Japan’s seniority system, lifetime employment, and other aspects are viewed as “premodern feudal relics.”[66] However, these are also “noteworthy characteristics of Japanese management,” which can be explained as “a device that has been meaningful and has contributed to the development of Japanese companies and the economy.”[67] Although Sazō’s emphasis on the unity of Japanese organizations may sound passé in 2025, recent studies have shown that team trust is the foundation for innovations.[68]

Sazō and Drucker both understood that Japanese management reflects social and cultural values that have shaped Japanese society. They were aware that cultural identities were important, but they encouraged the incorporation of foreign elements into organizations. Sazō was open to modifying how the Western model affected the localized version of Japanese business organization:

Don’t deny the stock organization. We are in a test tube that we generate our own way. In a test tube, if human beings are capital, we will do it our own way. You think gold is capital, but let’s look at Idemitsu. We will show you that you will improve the way the stock organization should be.[69]

Both Sazō and Drucker thought that the legitimacy of leaders’ governance resides in their morality and heart, as they decide what to do, what not to do, and how to change things in their organizations. Drucker embraced the stylistic diversity that was accomplished in the austere ink drawings that depicted landscapes, birds and flowers from the Muromachi period and the Zen paintings that were fueled with spiritual wisdom and humor by Hakuin and Sengai; literati paintings of plants, bamboos, and landscapes full of life; and other artists known for their unique artistic endeavors with dynamic and meticulous executions by Jakuchū and Shōhaku, to name a few. Drucker’s core values of unity in diversity and the meaning of persona, looking in the mirror, are all projected on his collection and management principles.

According to Cecily Drucker, her parents left no last words about the destiny of their collection. Linkletter, who was close to the Druckers in their later years, noted that the couple was very private and kept their collection relatively unknown to the public. Although they contributed and offered advice to museums, they were not eager to take on official roles, such as board members. They stored their paintings at Pomona College, yet the school didn’t inherit the collection. Peter and Doris Drucker must have thought about the destiny of their precious collection and the morality of collectors, e.g., Benjamin’s concerns about saving artwork from the market. In the end, there might be both rational and ethical decisions to be made as to where the whole collection should be permanently housed. Drucker’s management principles and practices have been well-received in Japan, and he was a mentor to many business leaders in the country. He developed friendships with businesspeople and art historians. The Drucker School of Management was renamed the Peter Drucker and Masatoshi Ito School of Management, in honor of Ito’s contribution to the school. The bereaved family was relieved that an anonymous Japanese company had a spiritual tie resonance with Drucker’s management philosophy and wished to preserve the entire collection as the embodiment of the collector’s vision of human society.

The year after Doris Drucker passed away in 2014, the couple’s collection was exhibited at the Chiba City Museum of Art. The whole Drucker collection of 197 art pieces was then acquired by the above-noted Japanese company and entrusted to the same museum. In Japan, Sazō’s and the Druckers’ whole collections have been kept intact and on public view. It suggests that their credos about moral duty inspired the further actions that honored their ideals: Drucker’s idea of management as a liberal art and Sazō’s aesthetic of business as focused on creativity, beauty, and endeavor.

Both the Sazō and Drucker collections will continue to remind us of the core values of humanity and organizations. How is a functioning society possible in the 21st century? In his quest for the well-being of workers, Drucker relied on non-profit organizations, whereas Sazō trusted in his company’s family principle. Each man followed the social reality and social values in his own country: in the United States in the 1990s and in Japan up to the 1980s. The role of non-profits became increasingly significant in the modern city just as Drucker predicted, and the logic of Ie is not completely disappearing. There is a never-ending flow of change and continuity in Japanese organizations. Change in social values is slow, but it would be achieved by Drucker’s insistence upon “what makes Japan more Japanese.” Sazō posed the same question when he designed the Idemitsu Museum of Arts: He not only wanted to show the public the immense amount of art in the collections, but also to present the spectacular view of the outer garden of the Imperial Palace through the enormous windows from the museum’s lounge. Socio-cultural values matter in management principles because management is engaged with each individual in situ, where he or she concretely is, and change is possible only if each person faces and defines reality on his or her own.

When we look at the art collections left by Sazō, the “Shopkeeper,” and Drucker, the “Socioecologist,” we can sense their fascination with and great tolerance for human beings. Along with noble and anonymous minds that were expressed in Karatsu ware, ink drawings by Zen monks, and literati paintings, Drucker and Sazō’s art collections as a whole suggest their vision of humanity and their transdisciplinary philosophy of management. If one can define one’s reality in conjunction with cultural values, one can find a rational way to reinvent society, while recognizing that a moral cause is essential to the pursuit of one’s goals. The quiet and private moments in which Drucker and Sazō confronted each work of art were invaluable to them in their pursuit of the self-fulfillment of knowledge workers and the functioning of society through their operations, whether the Ie (family/house/clan) or NPO, dealing locally with the world’s issues and crises.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank management scholars at the modern management workshop (held December 26, 2023, in Atami, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan) for their opinions on an earlier version of this paper. I also appreciate the invaluable advice and input I received from Karen E. Linkletter. This study began with the author’s acquaintance with Shiga Hirohito, affiliated with Idemitsu Kosan Co., Ltd., who pointed out the similarity shared by Idemitsu’s management policy and Drucker’s writings. I am also grateful to the Idemitsu Museum of Arts and the Chiba City Museum of Art for granting the use of their artwork images.

According to Suzuki Daisetz, Eisai visited China twice and brought the teaching of the Rinzai Zen sect of Buddhism to Japan. He established the Kenninji Temple in Kyoto, Jufukuji in Kamakura, and Shōfukuji in Hakata, where Sengai held abbotship. Suzuki, T. Daisetz. (1971) Sengai, The Zen Master. Faber and Faber Limited, 75; It is interesting to note that the tea ceremony offered a special meeting place because each guest had to disarm before entering the tea house. A tea ceremony itself is a total work of art, a multi-sensory experience of a simple yet refined interior and exterior design of the tea house, tea bowls, natsume (tea caddy), a hanging scroll, and other items are all specially arranged for each occasion. As the guests are having a cup of tea, they are also entertained by art objects, carefully chosen by the host. See Okakura, Tenshin. (1906) Book of Tea.

Tanaka, Hisao. (1981) Bijutsuhin Idōshi, Kindai Nihon no Korecta-tachi [History of Japanese Art in Transitions, Collectors in Modern Japan]. Tanaka discusses major art collectors in modern Japan and how artworks left the country before and after the war. Masuda’s collection was unfortunately dispersed after the Second World War, when the new law imposed a heavy tax on his collections. The tax was too burdensome for the bereaved family to pay.

Kuroda, Taizō. (1983) “Nihon no Kaiga [Japanese Paintings]”, Asahi Shinbunsha (ed.), Kokaratsu to Idemitsu Bijutsukan [Old Karatsu Ware and Idemitsu Museum of Arts], 80.

Drucker, Peter F. (1986) “[Our] Japanese Art,” Drucker Collection: Masterpieces of Suibokuga Exhibition, Osaka Municipal Museum of Art, Nihon Keizai Shinbun (no pages).

Ibid.

Kawai, Masatomo. (1986) “Suiboku Paintings of the Muromachi period in the Drucker Collection,” Drucker Collection: Masterpieces of Suibokuga Exhibition, Osaka Municipal Museum of Art, Nihon Keizai Shimbun (no pages).

Drucker observed “polarity” throughout Japanese culture. See Peter F. Drucker (1979) “A View of Japan through Japanese Art” in John M. Rosenfield, ed., Song of the Brush, Japanese Paintings from the Sansō Collection, Seattle, WA: Seattle Art Museum (no pages).

Drucker. (1986) “[Our] Japanese Art”; Kawai (1986) “Suiboku Paintings”; Wakisaka, Atsushi. (1986) “Suiboku paintings of the Momoyama and Edo periods in the Drucker Collection,” in Drucker Collection: Masterpieces of Suibokuga Exhibition, Osaka Municipal Museum of Art, Nihon Keizai Shimbun (no pages).

Drucker’s good teachers were art historians: Tanaka Ichimatsu, Matsushita Takaaki, Shimada Shūjiro (Princeton University), J.M. Rosenfield (Harvard University), Sugawara Hisao (Director, Nezu Museum of Art), and art dealers: Setsu Inosuke, Yabumoto Sōshirō, and Yamauchi Chōzō. See the detailed correspondence and interview articles in the exhibition catalogue, Masterpieces from the Sanso Collection: Japanese Paintings Collected by Peter F. and Doris Drucker (2015). Kawai, Masatomo. ed., Bijutsu Shuppansha, Co., Ltd., Chiba City Museum of Art, 186-199.

Idemitsu, Shōsuke. (1998) “Chichi, Idemitsu Sazō to Sengai [Father, Idemitsu Sazō and Sengai]”, Sadō Zasshi, Vol. 62, No. 2, pp. 27.

While Sazō had a business in Manchuria, there was an antique shop in front of his office. The shop owner told Sazō, “The high price of antiques doesn’t necessarily signify its true value; see it with your eyes and take what you like,” and he followed the words in developing his collection. Idemitsu, Sazō. (1975) Eien no Nihon [Eternal Japan], Heibonsha, 276-277, 288-289.

Interview with Cecily Drucker by the author, E-mail reply: August 25, 2023.

Idemitsu Museum of Arts (2004) Shuūshūka Idemitsu Sazō no Kokoro, Idemitsu Collection Tanjō 100 Shūnen [Collector, Idemitsu Sazō’s Heart: The 100th Anniversary of the Birth of the Idemitsu Collection] Idemitsu Museum of Arts, 87,97-99.

Sazō. (1975) Eien no Nihon [Eternal Japan], 279-281.

Drucker. (1986) “Our Collection of Japanese Paintings” (no pages).

Sazō. (1975) Eien no Nihon [Eternal Japan],175-76.

Suzuki. (1971) Sengai, The Zen Master, 1.

Sazō. (1975) Eien no Nihon [Eternal Japan], 175.

Following the teachings of Suzuki Daisetz, Sazō often argued that Japanese morality is different from Western morality. They saw morality as a persistent cultural value. They understood morality as being largely based on the Western religious background of valuing absolute agreement with God, such as in the Ten Commandments. In their view, morality in the West is grounded in the establishment and observance of laws, regulations, and organizations enforced by conquerors and emperors in order to govern their people. By way of contrast, Daisez and Sazō thought that morality in Japan naturally emerges from one’s conscience. For Sazō, morality persists at the core of each nationality and ethnicity. Sazō (1975) Eien no Nihon [Eternal Japan], 81, 176-79, 186-87.

Linkletter, Karen E. (2024) Drucker and Management, Routledge, 44-45.

Karen E. Linkletter, interview by the author, online meeting January 5, 2025.

Yoshizawa, Tadashi. (1969, 1994) “Nanga [Southern Painting]”, in Genshoku Nihon no Bijutsu: Nanga to Shaseiga, vol.19 [Japanese Paintings: Southern Painting and Sketched Painting vol.19] Tokyo: Shogakkan, 168-69.

Ibid., 188. Zen school, Ohbaku, had an influence on culture in the Edo period. Ike Taiga and other literati painters learned from the paintings and calligraphy that were made by the Ohbaku monks who came from China. See, Kyoto National Museum (1993) Ohbaku no Bijutsu: Edo Jidai no Bunka wo Kaetamono [Arts of Ohbaku: It changed culture in the Edo Period] Kyoto National Museum.

Idemitsu, Sazō. (1969, 2013) Hatarakuhito no Shihonshugi [Capitalism for Workers], Shunjusha Co., Ltd., 22.

Sazō. (1975) Eien no Nihon [Eternal Japan], 123.

Drucker, Peter. (1994) Adventures of a Bystander, Routledge.

Suzuki. (1971) Sengai, The Zen Master, 17.

Murayama, Nina. (2014) “Peter Drucker – Wien ni okeru Sōgōgeijutsu Kyōiku [Peter Drucker, Total Arts Education in Vienna]”, Annual Report of the Center for Teaching Education Research, Vol.4. Tamagawa University, pp.67-75; Murayama (2015) “Drucker – Geijutsu tositeno Kyōiku [Peter F. Drucker in Vienna: Teaching as Art]”, Annual Report of the Center for Teaching Education Research, Vol.5. Tamagawa University, pp.55-64.

Drucker believed that performance-based compensation was essential, but the foundation was that knowledge workers should be motivated by goals. Thus, the mid-1980s had already warned of the enormous amount of executive compensation. Rosabeth Moss Kanter (2009) “Drucker ni Manabubeki Koto [What Would Peter Say?]”, Translated by Izumi Yuko, DIAMONDO Harvard Business Review, Vol. 34, No.12 (December) pp.12-13.

Murayama, Nina. (2023) “Peter F. Drucker to Idemitsu Sazō, Suibokuga no Juyō to Manegiment” [Peter F. Drucker and Idemitsu Sazō, Their Receptions of Japanese Ink Drawings]" STUDIES IN ART, Vol 15, Bulletin of Tamagawa University, College of Arts, pp.1-16.

Drucker, Peter. (1979) “A View of Japan through Japanese Art,” John M. Rosenfield ed. Song of the Brush, Japanese Paintings from the Sanso Collection, Seattle: Seattle Art Museum (no pages).

Idemitsu, Sazō. (1971) Nihonjin ni Kaere [Know Your Root As Japanese], Diamond sha, 176.

Idemitsu, Sazō. (1963) “Minzokukei-Keieisha Idemitsu Sazō ni Kiku” [Interview with a Folk Leader Manager Idemitsu Sazō], Economist, Vol. 41, pp. 60-64.

One misquoted example of Drucker’s words is “Culture eats strategy for breakfast,” but as the Drucker Institute notes, Drucker never said it. Drucker, Peter. (1991) “Don’t Change Corporate Culture – Use It!” The Wall Street Journal, Thursday, March 28.

Drucker, Peter. (1978) “Japan: The Problems of Success,” first published in Foreign Affairs; reprinted in Drucker (1993) The Ecological Vision: Reflections on the American Condition, Transaction Publishers, 396.

Drucker, Peter. (1969) “Management’s Role” Keynote address given at the 15th CIOS International Management Congress, Tokyo, printed in Drucker (1993) The Ecological Vision, 137-51.

Sazō. (1975) Eien no Nihon [Eternal Japan],128.

Murayama, Motofusa. (1977) Keiei Bunka Ron [Management Culture Theory] Gyosei, 15-31.

Kuroda. (1983) “Nihon no Kaiga [Japanese Paintings]”, 56-62.

Drucker, Peter. (1979) “A View of Japan through Japanese Art,” quoted in The Ecological Vision, 374.

Ibid.

Kikkawa, Takeo. (2012) Idemitsu Sazō: Ougon no Dorei Tarunakare [Idemitsu Sazō: Don’t be Enslaved by Gold] Minerva Shobo, 21-27.

Linkletter. (2024) Drucker and Management, 43-49.

Ibid.

Idemitsu, Sazō. (1966, 2013, 2016) Marx ga Nihon ni Umaretara [If Marx were born in Japan], first published by Shunjusha, new edition Kodansha 2013, Kodansha Bunko, 44-45 and 142-45.

Sazō. (1969, 2013) Hatarakuhito no Shihonshugi [Capitalism for Workers], 102; A Japanese literary, Natsume Sōseki pointed out at the time, there had been a misconception that individualism was the opposite of nationalism in Japan, and he emphasized that individualism in the Western context was about the freedom and duty as two sides of the same coin. When Natsume gave his lecture on “Watashi no Kojinshugi [My Individualism]” in 1914, World War I broke out in the same year when Sazō was 29 years old.

Idemitsu, Sazō. (1971) Nihonjin ni Kaere [Know Your Root as Japanese], 36, 131-32.

Inoue, Mayumi. and Tamai, Yoshiro. (2014) “Idemitsu Sazō no Rinen to Kobe Koutou Shougyo Gakkou no Kyoikusha [The management philosophy of Idemitsu Sazō and two teachers of Kobe Higher Commercial School]” Sangyo Kenkyu, vol.50, no.1.53-69.

Sazō. (1966, 2013, 2016) Marx ga Nihon ni Umaretara [If Marx were born in Japan], 152-53.

Mito, Tadashi. (1991) Ie no Ronri I, II [The Logic of Family I, II] Bunshindo; Murayama Motofusa observed it in his terms “Family System” in Murayama (1978) Culture and Management in Japan, Chiba Academic Press.

Mito, Ie no Ronri II [The Logic of Family II], 109. Some leading factory owners followed their own humanitarian principles in their treatment of workers.

Hazama, Hiroshi. (1991) Nihonteki Keiei no Keifu [History of Japanese Management]. Hazama pointed out that lifelong employment, seniority system, and welfare are the major values of Japanese management. He observed that after World War II, Japanese companies continued to embrace the welfare of their workers in management. See Mito (1991) Ie no Ronri II [The Logic of Family II], 220-229.

Mito, Tadashi. (1982) Zaisan no Shūen: Soshiki Shakai no Shihai Kōzō [End of Property – Structure of Control in Organizational Society], Bunshindo, 142-44.

Drucker, Peter F. (1973, 1974, 1985, 1993) Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices (New York and London: Harper Business edition, 1993; HarperCollins Publisher, Inc., 1973, 1974; Harper Colophon edition 1985), 725-727.

Mito. (1991) Ie no Ronri I [The Logic of Family I], 191.

Idemitsu, Sachiko. (2019) Idemitsu Sazō to Sengai - Bi Ni Riido Saretekita Jinsei - [Idemitsu Sazō and Sengai – Life led by the Beauty] Kokuminkaikan sōsho.

Drucker, Peter. (1990) Managing the Non-Profit Organization: Principles and Practices, Harper, 168.

Ibid., 184, 203. Drucker also wrote a non-profit executive to ask, “What am I doing that helps you with your work? What am I doing that hampers you?” This supportive attitude exhibits servant leadership. There is a Japanese term “work” and “working” as hataraku literally means to make others easy. The origin of the notion of work is about working in a team so that things are done easily.

Tenbo, Akihiko. “Watashi No Rirekisho 1, 4, 6, 7, 22 [My Resume 1, 4, 6, 7, 22]” Nihon Keizai Shimbun, April 1, 4, 6, 7, 23, 2020.

While Sazō was alive, there was a public-interest corporation system in Japan, but the legal system was inadequate. Sazō passed away in 1981, 17 years before the enactment of the Law for the Promotion of Specified Non-Profit Activities (NPO Law) in 1998.

Drucker, Peter. (1998) “On Civilizing the City,” in Peter F. Drucker (2002) Managing the Next Society, Truman Talley Books, St. Martin’s Griffin, 230-232.

Drucker. (1990) Managing the Non-Profit Organization, 112.

Drucker. (2001) “The Next Society” in Drucker (2002) Managing in The Next Society, 241.

Paul Holdengraber discusses what collecting in the modern city meant to Walter Benjamin. In “A Berlin Chronicle,” the young philosopher and cultural critic Walter Benjamin characterized Berlin as “the theater of purchases” where the modern city offered certain stores with particular items of fine quality, such as hats, suits, or shoes. See Holdengraber, Paul. (1992) “Between the Profane and the Redemptive: The Collector as Possessor in Walter Benjamin’s ‘Passagen-Werk’” History and Memory, Vol. 4, No.2 (Fall-Winter, 1992), pp.96-128. Drucker left behind such bourgeois security and comfort, and even a nostalgic feeling, when he departed his native Vienna in 1927. Benjamin himself was an ardent collector of books. He cast light on anonymous collectors whose seemingly trivial collections, such as streetcar tickets or stamps, were ephemeral items that were forever saved from ordinary drudgery. In this specific sense, Hannah Arendt noted that Benjamin’s attitude was akin to that of the revolutionary, that is, liberating an object from its use value, as Holdengraber noted. Inspired by Kant and Schopenhauer, Benjamin was preoccupied with an object of contemplation, that is, seeking beauty removed from “functional context.” Benjamin also recognized the tactile instincts of collectors of books, and private ownership was important for such an intimate experience. It is uncertain if Drucker conceived such a revolutionary mindset, but he embraced and appreciated the tactile, sensory quality of his ink paintings and literally lived with them by hanging several scrolls in his house at Claremont in California.

Suematsu, Ryōsuke. (1983) “Idemitsu Bijutsukan – Oitachi to 17-Nen [Idemitsu Museum its beginning and 17 years]” in Kokaratsu to Idemitsu Bijutsukan [Kokaratsu Ware and Idemitsu Museum of Arts], 125.

Murayama, Motofusa. (1997) Keieibunka Ron - Fueki Ryuko [Management Culture – The Timeless Flow of Change and Continuity], Bunshindo, 346.

Ibid.

Satō, Yamato. (2024) Shin Nihonteki Keiei Ron [New Japanese Management Theory] Bunshindo, 167-69.

Sazō. (1975) Eien no Nihon [Eternal Japan], 16.

_pointing_at_the_moon_*_ink_on_paper._54.1x60.4cm__idemitsu_museum_o.jpg)

*__round_fan_mounted_as_a_hanging_scroll__ink_and_color.tif)

_pointing_at_the_moon_*_ink_on_paper._54.1x60.4cm__idemitsu_museum_o.jpg)

*__round_fan_mounted_as_a_hanging_scroll__ink_and_color.tif)