I. Introduction

In the summer of 2022, the topic of “quiet quitting” cropped up with increasing frequency in public discourse. It showed up in Forbes, Bloomberg, and many other venues. All one must do is enter “quiet quitting” into the Google search bar to see this. The articles, for the most part, reflect on essentially the same thing: People seem to be tired of being driven to work harder and harder by companies and their immediate bosses if they conclude that neither the company nor the boss cares about them. In response, quiet quitters appear to be doing the least they can “get away with” in exchange for their pay.

It will be argued in what follows that the only new thing about “quiet quitting” is that people are talking about it in increasing numbers in public fora. It is not as if it has never happened before. Also provided is an argument based on a synthesis of recent research and theory, which suggests a solution to the problem. This solution has long been known and much discussed. It is called “good” leadership, or in terms that will be used in this paper, being a “good” boss.[1] The question becomes: what is it to be a “good” boss? More importantly, why does it work?

This paper addresses these questions by first discussing what the “quiet quitting” fad is reacting to. Then it will connect quiet quitting to the results of the last three Gallup reports (2013, 2017, 2022) on the state of the American workplace. To illustrate the connection between Gallup’s findings and the phenomenon of quiet quitting, the “safety zone” concept is introduced and explained. Next, a relatively new approach from the discipline of economics is introduced and incorporated into the discussion. It will show why and under what circumstances it is rational for workers to do more than they can “get away with” when on the job. Then it is argued that the responsibility for dealing with the problems of “quiet quitting” and its variants falls squarely onto management. Finally, a solution to the problem is proposed. It boils down to how “good” bosses do their work as opposed to “bad” ones.

II. Quiet Quitting

As noted above, references to the “quiet quitting” phenomenon began to pop up in the media during the summer of 2022. By early August, Wikipedia had already included an article on quiet quitting with a reference history that went back to July 2022 before changing the title to “Work-to-Rule,” specifying that “quiet quitting” was a special case of that. But though the term is new, the phenomenon it introduces is not new at all. Michael Hiltzik, a business columnist for the Los Angeles Times, wrote:

The idea [behind quiet quitting] is that employees who are exhausted or frustrated by ever-increasing duties and ever-longer demands on their time and are feeling unappreciated ratchet back to the bare minimum of their job duties. (Hiltzik, 2022, para. 5)

The title of Hiltzik’s article, “Quiet quitting is just a new name for an old reality,” accurately reflects its content. It has been around for a long, long time. It is just not very “quiet” these days.

Let us be clear: Quiet quitting does not mean failing to comply with the requirements of one’s job. It means doing the least one can get by with to keep one’s job. “Work-to-rule,” of which quiet quitting is a special case, means doing what is specified in one’s job description, no more, no less. In turn, the concept of working to rule is not new either. Sociologist Reinhard Bendix, in his magisterial Work and Authority in Industry (1956), wrote:

To be effective, authority depends on the assumption that subordinates will follow instructions in terms of the spirit rather than the letter of the rules. Two things are implied here: that the subordinate will adopt the behavior alternatives selected for him, and that he will give his “good will” to carrying out his orders. As this formulation suggests, “good will” involves judgment and initiative. . .[which can be] withheld by a “withdrawal of efficiency”. . . a slavish clinging to the letter of the rules…(Bendix, 1956, p. xlv)

Bendix wrote this passage as part of a discussion of what he termed “strategies of independence.” The slavish adherence to “the rules” was one way workers resisted management that, in their views, demanded more than the workers believed was “fair.” Significantly, Bendix began the passage mentioned above with the prescient statement: “All authority relations have in common that those in command cannot fully control those who obey” (1956, p. xlv).

The phenomenon of quiet quitting has caused concern among executives for obvious reasons: If people stop going above and beyond the minimum requirements of keeping their jobs, it will likely have a deleterious effect on unit costs and, thus, on profit margins. In an article published in Planet Money on September 13, 2022, Greg Rosalsky and Alina Selyukh noted that government data (from the Bureau of Labor Statistics) shows “an historic drop in productivity over the last two quarters” (Rosalsky & Selyukh, 2022, para. 10). This may be due to the post-COVID recovery with its concomitant tight labor market. In this connection, the authors quote Julia Pollack, the chief economist at ZipRecruiter:

“With layoffs and firings at a record low… people have unprecedented job security,” says Julia Pollak, chief economist at the job-search website ZipRecruiter. “And so the risk of termination is lower. And that’s also why the incentive to work harder is reduced. The consequences of being found to shirk have become much smaller. One, because companies can’t afford to fire people. And two, because there are so many alternatives out there if you do lose your job.” (Rosalsky & Selyukh, 2022, para. 9)

If Pollack’s statements are true, one consequence of an economic downturn, which may be at hand as this is being written (November 2022), might be a gradual disappearance of “quiet quitting,” or else it will go back to what it has been in the past—invisible, but still there and not talked about. The threshold of effort required to keep one’s job will no doubt rise, and the fad may disappear,[2] but the problem that underlies it will not go away as long as its root cause remains in place.

A hint of what this root cause might be is provided in Hiltzik’s reference in the quotation above to “employees who are exhausted or frustrated by ever-increasing duties and ever-longer demands on their time and are feeling unappreciated.”

III. What the Gallup Reports Say

In 2013, 2017, and 2022, the Gallup Organization published reports on the state of the American and, in 2022, the global workplace. In 2013, it published an analysis of the data it had collected over the previous decade relative to the relationship between “engagement” and productivity. It found that, in the American workplace, 30% of workers were “engaged,” 52% were “disengaged,” and the remaining 18% were “actively disengaged.” The Gallup Report provided working definitions of these categories: “Engaged” employees are committed to the objectives and missions of their organizations. “Disengaged” employees are tuned out and come to work for their paychecks. The “actively disengaged” go out of their way to do the least they can get by with and sometimes even perform acts of sabotage. For the purposes of this paper, the quiet quitters fall into the second category. In the 2017 report, Gallup reported that 33% of workers were engaged, 51% were disengaged, and 16% were actively disengaged. In 2022, Gallup surveyed the whole planet and used a different set of measurements, keeping only “engagement.” In this respect, the American workplace remained stable, with 33% engaged, as was also the case in 2017. That means 67% were either disengaged or actively disengaged. Any way one looks at it, at least half of America’s workforce could be considered “quiet quitters.”

Years before the Gallup surveys, when working as an organizational consultant for Pacific Bell, I presented to a group of six high-performing mid-level operations managers. All but one lacked college degrees, though all were quite intelligent and had managed to acquire educations through their own efforts. They had worked their way up from the “tools,” as they used to say, having begun their careers as technicians. One of them later became a vice president of operations for another large telecommunications company, and two of the others became district and division managers. They were competent, expert insiders who knew whereof they spoke.

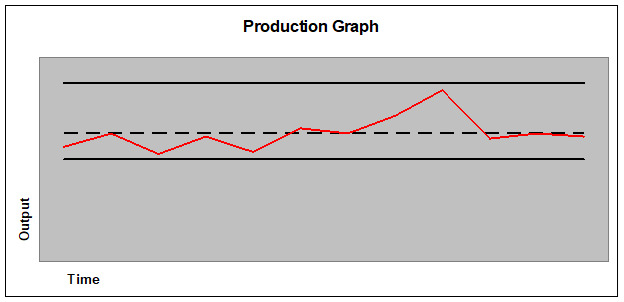

I used the graph in Figure 1 below to structure the conversation we had:

This production graph represents the variation in output over time of an individual or group. Assume for the moment that it represents an individual’s performance over time, though it could also represent the output of a group. The output part of the graph could be anything: widgets per day, number of calls taken per hour, or even abstract things like “management support” for a company initiative. The jagged line in the middle represents actual performances over time. The “Upper Limit” line represents the barrier that this individual’s performance rarely or never breaks. This could be equivalent to the maximum effort the individual is capable of, but it is often socially defined as part of a “peer group standard.” The “Lower Limit” represents the threshold of what the boss considers acceptable. The dashed line is the individual’s (or group’s) average output. It results from following a set of rules, of which the following two are important elements: Don’t cross the upper line, or you may get pressure from your peers. Stay above the lower limit, and you won’t get adverse attention from your boss. In between these limits is the “Safety Zone.”

The managers to whom this presentation was made were asked to create general profiles of workers at the top, middle, and bottom of the Safety Zone. We agreed to call the ones who bumped the top of the graph “careerists” or “high performers.” We agreed that, while the top line was rather fluid for managers and other professionals, it was quite real—and often well-defined—for non-managerial employees, especially those (both blue- and white-collar) who are paid by the hour. These workers avoided breaking it so as not to incur the hostility of their peers. This apparently intransigent fact has shown up in a number of classic studies (Burawoy, 1979; Mayo, 1933; Roy, 1952, 1953). It was the bane of Frederick Taylor (1912), the father of “Scientific Management,” who decried the work of rate-setting as “soldiering.”

That the upper limit to the Safety Zone fell short of workers’ maximum potential was considered common knowledge by these managers and many others in several industries with whom I had this discussion in my decades of experience as a consultant. But with or without this generally invisible but, often enough, quite real upper limit, employees in the higher reaches of the Safety Zone would have likely shown up as “engaged” in the Gallup analyses.

We somewhat jokingly referred to the ones at the bottom as “wage criminals”—workers who did the absolute least they could get by with, though they sometimes got fired anyway. Being a wage criminal—Gallup would probably classify them as “actively disengaged”—was risky even in a big quasi-monopoly with union protections.[3]

We referred to those safely nestled between the high performers and the wage criminals as “accommodators.” They did what they were told, did not complain or do anything else to draw attention to themselves, and when not tapped to work overtime, they were in the company’s parking lot at 5:01 PM, igniting their engines and beginning their commutes home. They were living out their “work/life balance.” To sustain their lives while at work, they stayed in the middle reaches of the Safety Zone, preferring relative invisibility to “getting ahead” or “getting in trouble.”

Because they made up at least half of the workforce, their output would have a preponderating impact on the average output of a typical group. To significantly increase the group’s output, the support of these accommodators was deemed essential by the team with which I was working. Were the accommodators quiet quitters? They were certainly quiet enough. But had they actually quit? That is debatable. They were surely working. But were they working as hard as they might have? That is the question.

IV. What Economists Have to Say

The behavior of the quiet quitter would be perfectly comprehensible to traditional economists, such as the late Oliver Williamson (1986; 1981) or Armin Alchian, who, in his introductory economics text (with William R. Allen, 1977), wrote, “Whatever their talents, people can be trusted to shirk” (Alchian & Allen, 1977, p. 218). Based on traditional utility theory, Alchian and Allen’s statement makes sense: Effort is a material resource a worker possesses. If a worker’s income is held constant, he or she maximizes their utility by exerting the least amount of effort they can “get away with” to collect their pay, with which they purchase other material resources. To work any harder than that is irrational because it represents an expenditure of a material resource—the worker’s potential supply of productive effort—with no offsetting material gain. That is, the workers would not be maximizing their utilities. Ironically, those quiet quitters who work just hard enough to stay off management’s radar are, from an orthodox economist’s point of view, rational.

If we begin by assuming that workers are rational, the question becomes how to get them to make rational decisions to supply more productive effort than they can “get away with.” For Williamson (1986, pp. 32–53; 1981), who received the Nobel Prize in Economics (2009), this would entail raising the lower limit of the Safety Zone, enforcing it by means of surveillance, applying penalties for failure to comply, and promising material incentives—pay raises and bonuses—to “high performers.” Note that, in Williamson’s world, workers have not changed at all. They’re still doing the least they can get away with; it’s just that this “least” can be increased by managerial surveillance and corrective action.

Alternatively, direct financial incentives could motivate incremental productive effort, as was famously advocated by Frederick Taylor (1912). The latter approach works in some cases—e.g., commissions for salespeople or piece-rates for factory workers—but is difficult to apply when responsibility for output is unclear, either because of intrinsic measurement problems or because the output is the result of joint effort, and it is hard to say who did what and how much. But when incentives are applicable, workers will supply more effort than they can get away with as long as the increment in pay exceeds the value—to them—of the incremental effort it takes to get it.

For the sake of completeness, it should be added that if a worker enjoys his or her job, he or she will supply more—possibly far more—than the bare minimum because they get utility—some form of “feel-good”—from the work itself. This utility may far exceed the material value of their pay. Consider as examples the work of a professional surfer or musician.[4] The surfer and the musician get intrinsic joy—gratification—from their work regardless of whether they are paid. Since this joy is experienced through physical correlates, it is a form of utility. Thus, the surfer or the musician gains utility from surfing (as long as it is a good day for waves) or from playing his/her instrument independently of being paid to perform these activities.

The evolution of the economics of the organization did not end with Oliver Williamson. Economists George Akerlof and Rachel Kranton (2000) proposed a utility function that included, in addition to the “ordinary economic goods”—material things that can be purchased in “markets”—something they dubbed “identity utility.” Identity utility is the satisfaction human beings gain from conforming to the norms of a social category or group with which they “identify.” We identify with a social category or group when we seek to look good to others in our preferred social categories or groups. When we do, we feel good about it. When we do not look good to them, we feel bad about it. The elation that comes from feeling good in this context has physical correlates. The anxiety or guilt that comes from feeling bad about oneself also has its own generally unpleasant physical correlates. Utility is all about “feeling good” or avoiding “feeling bad.” Hence, it is reasonable to regard feeling good or bad, based on looking “good” or “bad” to relevant others, as a legitimate form of utility. Therefore, having chosen a category or group to identify with, we increase our utility when we conform to the norms that characterize them because feeling good about anything increases our utility as long as the cost of our effort (a reduction in utility) is less than the feel-good attained from getting it.

Ten years after publishing their ground-breaking paper, Akerlof and Kranton published a short but profound book, Identity Economics (2010), in which they provided a number of applications of the concept of identity utility. One of them is particularly germane to the focus of this paper: They addressed the question of why workers will, under certain circumstances, and independently of how much they are paid, exert more productive effort than they could “get away with,” as a traditional economic model would assume. To accomplish this, they made a distinction between “insider” Labor, which consists of individuals who are committed to the norms and goals of the Firm, and “outsider” Labor, which consists of individuals whose orientation to work resembles that of the “rational” agent of orthodox economics. Insider Labor supplies “high” effort; outsider Labor supplies “low” effort. Insider Labor sees itself as “building a cathedral;”[5] outsider Labor is just laying bricks in exchange for a paycheck. In that discussion, the authors argued that, in order to secure equivalent effort from outsiders, they would have to be paid a premium since they only react to material incentives (2010, pp. 42–43). Therefore, it is incumbent on the firm’s management to try to convert outsiders into insiders (2010, p. 59). We note, in passing, that “quiet quitters,” “accommodators,” and “outsiders” are close equivalents. Thus, we may surmise that whatever would work to turn outsiders into insiders would also work for quiet quitters.

Before addressing how this can be done, note that Akerlof’s and Kranton’s expanded utility function implies that the only way to get people to do “more than they could get away with,” short of increasing management control or offering financial incentives, both of which incur incremental monetary costs, is to make doing “more than that” a moral issue. Insider Labor conforms to a different set of norms than outsider Labor. It is no longer doing what one does just because the boss says so. It is about doing what one does because one believes it is the right thing to do, according to the norms of the entity with which one has chosen to identify. Insiders would not look “good” or could even look “bad” to themselves if they did otherwise. This is another way of saying that insiders are committed to the norms and objectives of the organization or, short of that, the norms and objectives of their work unit.

With these arguments in hand, the question for management, particularly for the leadership component of its job, is how to secure commitment to these norms and objectives.

V. How Bosses Matter

Recalling our assumption that workers (and human agents in general) are rational, the question remains: How can Labor (i.e., anyone who has a boss) be induced to rationally decide to do more than they could safely “get away with?” Herbert Simon (1945) argued that Management should take actions that affect the “premises” of Labor on the assumption that human agents, in general, are rational, albeit that this rationality is “bounded.” They are rational, nonetheless. If Management succeeds, Labor will use its modified premises to make personally rational decisions that also benefit the Firm, even when Labor is not under Management’s surveillance. The question then becomes: what actions can Management take to gain this outcome?

To address this question, let us consider the work of the “boss.” In 2010, Robert Sutton of the Stanford Business School published Good Boss, Bad Boss (Sutton, 2010). His book illustrates in colorful detail the externalities to society, the effects on the Firm’s turnover costs, and the impact on productivity caused by “bad” bosses. The difference between “good” and “bad” bosses is confronted when one asks how they go about modifying Labor’s premises.

“Bad bosses” can be summarily characterized as “Theory X” (MacGregor, 1960/1985) leaders who have a decided preference for the “stick” over the “carrot.”[6] This type of leader modifies the premises of his subordinates through a combination of orders, threats, and rewards. He or she tells them what to do and often how to do it, regardless of whether they “know better.” While this conversation with Labor is sometimes bilateral, it is mostly a one-way conversation. This type of boss prefers to make unilateral decisions. He or she talks; Labor listens and complies. Labor’s right to speak is generally limited to asking questions to clarify what the boss wants.

But this alone does not necessarily make a “bad” boss.[7] If the boss is really “bad,” he or she might give credit for successes to his or her “favorites” (allocating such “carrots” as they have to them) rather than where it is believed by other subordinates to be due. Bad bosses might take credit for their subordinates’ work without acknowledging them. They may try to “bury” the more able among them when presenting their unit’s accomplishments to higher-ups. If the boss is bad enough to be considered “toxic” (Frost, 2007), he or she might verbally abuse subordinates in private or public settings, presumably to “motivate” them to follow the boss’s orders. Prima facie, this would adversely affect their identity utilities. To avoid this loss of identity utility, they will try to follow the boss’s orders, whether or not they believe them to be valid. In these ways, the bad boss seeks to modify Labor’s premises.

Now let us consider the work of “good bosses.”[8] The objective of the “good” boss is to take actions that increase Labor’s commitment to the objectives of the Firm. For Labor to commit to them, it must first understand the connection between the Firm’s well-being and its own. Assuming Labor has been educated about the connection between the Firm’s well-being and its own, the next task is to show Labor the alignment between the objectives of its particular work unit, for which the boss is accountable, with those of the joint well-being of the Firm and Labor. Without these connections to a larger purpose, the only remaining possible commitment of Labor to the Firm is its commitment to the boss’s orders, assuming that they are adequate translations of the Firm’s objectives.

Good bosses seek to persuade their subordinates to modify their premises. To do this, they invest effort in building relationships with their subordinates and show in their words and actions that they care about their well-being. Having established this, they are more likely to be trusted. They would then be able to inform their subordinates and be believed by them when they present a “vision” of a better future that is good for both the Firm and for Labor. Reflecting on recent research regarding the “good boss/bad boss” dichotomy, Katherine Shaw summarized: “Good bosses have some universal traits: they coach and teach and offer insight into the strategy of the firm and the worker’s career goals in light of that strategy” (Shaw, 2019, p. 1).

These observations suggest that good bosses seek to imbue the day-to-day activities of Labor with a purpose beyond that of merely receiving its pay. Good bosses attempt to secure Labor’s commitment to the “cathedral” it is building. It may still be laying bricks, but as long as it “cares” about the cathedral, the total utility it derives from its efforts exceeds the income utility it would derive from its pay if pay were its only incentive. Its commitment to the cathedral implies it is likely to do more than it might otherwise “get away with.” Just as importantly, once Labor is committed to its “cathedral”—whatever that might happen to be—it would look bad to itself if it failed to do the “right things”—whatever those happen to be. Thus, Labor would do the right things because if it did not, its loss in identity utility would exceed the subjective value of its saved effort. Thus, it would fail to maximize its utility.

It is reasonable to ask whether the difference between good and bad bosses has been measured. In fact, the impact of good versus bad bosses has been investigated in a small but growing body of work. Lazear, Shaw, and Stanton (2015) conducted research in which it was found that work teams with “good” bosses produced about 10% more than essentially identical work teams with “bad” bosses. Shaw (2019) analyzed the results of several recent studies, including the one by Lazear et al. (of which she was a co-author), and concluded that a good boss could get as much as 50% more output than a bad one.

Clearly, a large part of the difference between good and bad bosses consists of their engagement level with their employees. Consider again the comment by Los Angeles Times journalist Michael Hiltzik, who suggested that quiet quitters are “employees who are exhausted or frustrated by ever-increasing duties and ever-longer demands on their time and are feeling unappreciated.”

The keyword here might be “unappreciated.” How does Management make Labor feel “appreciated?” The short answer is “through engagement.” The simple secret to dealing with disengaged employees is to engage them in a bilateral conversation about what is good for them, what is good for the organization, and how that translates into their work objectives and goals. A “genuine” bilateral conversation is one in which each party is taken seriously by the other—and specifically, that the subordinate’s participation is not mere tokenism.

In its 2013 report, Gallup found that the difference in productivity between the top 25% of their sample, relative to “engagement,” and the bottom 25% was 21%. The sample was stratified by industry to ensure that apples were being compared to apples. The corresponding difference in profitability averaged 22%.[9] It also reported that when the ratio of “engaged” to “actively disengaged” was greater than 9.3, earnings per share were 147% of that of the competition.

Let us take a closer look at the last statement. Assume for simplicity that the merely “disengaged” comprised 0% of the workforce of a given firm. Then, if the “actively engaged” numbered 9.3 times as many people as the “actively disengaged,” the latter would comprise a bit less than 10% of the workforce. The actively engaged would number slightly more than 90%. Gallup found that when this ratio of actively engaged to actively disengaged was attained and assuming that the average competitor had the usual distribution of these types (30% engaged, 52% disengaged, and 18% actively disengaged, per the 2013 report), the firm’s earnings per share would be 47% higher than that of its average competitor. Note that this difference is not determined by physical technology. It is all about getting more from the organization’s human capital assets. For the most part, this means having “good” bosses who do what good bosses do: They educate, persuade, and care.

VI. Conclusion

This paper has attempted to show that the root cause of “quiet quitting” and its historical antecedents is the relationship between the “boss” and his or her subordinates, between Management and Labor. The only thing new about quiet quitting is that it has not been quiet lately, though this is likely to change. The problem, however, is likely to remain. It was here and in force long before the accommodating 50% became “quiet quitters” and will persist after the fad has ended. It is likely that they will just transform back into quiet “accommodators.” Time will tell.

What might Management do to move the accommodators to a space of genuine engagement, where they come to work caring about the well-being of the company and feel good about themselves for doing the right things, where they are less likely to pass their days running out the clock, carefully avoiding surveillance if they can?

Let us begin outside the Firm, so to speak, and work our way inward. Peter Drucker wrote that profit maximization could not in itself provide a business with a reason to exist. Beyond this, he wrote, “There is one and only one valid definition of business purpose: to create a customer” (Drucker, 1955, p. 52). To this, one might add as a footnote, “…and to sustain the customer’s commitment to its products.”

The customer could care less about whether the firm is or is not maximizing its profits. The customer cares about the value he or she receives from the firm’s products or services, which is a relationship between the customer’s personal utility, the price he or she has to pay in order to realize it, and the availability and price of substitutes. The purpose of business, therefore, is to satisfy the customers’ desires at a cost that is compatible with a feasible selling price relative to the customer’s other options. The selling price will be feasible if it also provides investors with a risk-adjusted rate of profit that is acceptable to them.

A critical task for Management is to educate Labor, so it can connect the dots between the customer’s wants, the shareholders’ requirements, its own daily efforts, its own material interests, and its identity. Management should do whatever it takes to get people to know what the right things to do are and make them want to do them. That is, Labor should want to do them because they believe they are the right things, not just because someone told them what to do. In fact, they might, and often do, prefer to tell themselves what to do. But they are more likely to tell themselves to do the right things if they can connect those dots. So, the first step is education.

But there is a step that must accompany this educational process. Taking our lead from the statement in Hiltzik’s article, this process begins with making employees realize they are “appreciated.” The solution is not just to make employees “feel” appreciated. That can easily devolve into shallow and readily detected attempts at manipulation, which can be ineffective and might even backfire. It is to actually appreciate them, to treat them like rational adults, to teach them, and when they have been sufficiently taught, to engage them in a bilateral conversation about how they should go about their work, framed in the context of a compelling, higher purpose. That means they have the right to speak with the correlative obligation of the boss to listen.

I realize that this is not a new thought. What is amazing to me is that, in spite of the plausibility of this approach, not just based on a growing body of research but on plain common sense and introspection, only a third of the American workforce is, by Gallup’s measures, “engaged.” The problem can be resolved. It is Management’s challenge to do so.[10]

To avoid confusion between the work of “leadership” and “management,” the following definitions are proposed: “Management” is the work of producing a plan; “leadership” is the work of securing the commitment of those whose actions are needed to implement it. Anyone who has subordinates is a manager, and every manager, with or without self-awareness, performs “leadership” work. More detail on this matter is presented below, in the section, “How Bosses Matter.”

There has been an explosion of articles on “quiet quitting” that are consistent with the observations cited in this paper. A partial listing of them includes those written by Constanz (2022), Bremen (2022), and Harter (2022), who posted articles in Bloomberg, Forbes, and Gallup.com, respectively.

To avoid misunderstanding of the scope of this analysis, the Safety Zone concept is meant to apply wherever people work under the surveillance of a higher authority, whether it is in the context of big business, small business, government agencies, or nonprofit organizations. By extension, it applies to both blue- and white-collar workers. The upper limit’s permeability is a function of the level of organization—informal as well as formal—of the workers.

The enjoyment of performing activities for their own sake, with or without pay, also characterizes many types of what Peter Drucker referred to as “knowledge work.” See Drucker (2008), especially pp. 183-190.

The “cathedral” metaphor is borrowed from an anecdote presented by Drucker (1955, p. 151).

The following characteristics of the “bad boss” are primarily parsed from Sutton (2010).

For example, if Labor does not know how to do its job, it might prefer to be closely managed until it masters it.

The characterization of “good” bosses is also parsed from Sutton (2010).

These numbers should be interpreted with care. An increase of a given percentage in output—say, 10%—does not imply an increase of 10% in profits. This would depend on the margin on sales, asset turnover, and the possibility that, in order to sell the incremental output, prices might have to be reduced. But the increment to profit, in practice, could be greater than 10% and, in fact, could be several times that figure.

Peter Drucker (e.g., 2008, pp. 287–291) used the words “trust” and “integrity” to describe the practices of effective managers, who are effective precisely because they engage their people as human beings, not as mere instruments of production.